Building a “Sustainable Sandbox” for Crypto

Exploring the mad science of regulatory innovation through regulatory sandboxes, no action letters, and safe harbors

As happens with every election cycle, some are left cheering, some left crying, and some not really caring either way. Well, look on the bright side. As the great pop rock group Semisonic once said, “Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end, yeah.”

The new Trump administration is expected to trigger a legal reset and systemic shift in policy around innovative industries. However, regulating sectors such as blockchain and AI is hard. How does one even begin to write laws for new industries without stifling their growth while at the same protecting consumers?

Enter: regulatory innovation!

Now, you may say, “I thought the law was designed to be slow-moving and therefore, is inherently antiquated?” That presumption is wrong. In fact, we have a legal tradition of innovation through many different devices, such as regulatory sandboxes (aka sandboxes), no action letters, and safe harbors. These tools create flexibility in old laws and regulations so the law can adapt to new products and services.

Such legal innovation serves as a crucial bridge, offering a dynamic way to allow regulations to keep up with technological advances. This is particularly pertinent in areas like digital assets. Regulatory innovation offers flexibility allowing laws and rules to evolve alongside technological progress. This gives emerging industries clear and actionable guidelines, thereby minimizing the risks of stifling innovation while simultaneously protecting consumers. By embracing regulatory innovation, we can address the inherent challenges of regulating new and fast-changing industries effectively.

One powerful tool is the regulatory sandbox—a policy framework for implementing regulatory innovation while maintaining oversight. However, current regulatory sandboxes are far from perfect for innovative technologies. The ideal regulatory sandbox should take aspects from other similar policy tools like safe harbors and no action letters to offer a more comprehensive approach.

In this article, we’ll explore how regulatory innovation tools like regulatory sandboxes, no action letters, and safe harbors can effectively regulate innovative industries such as blockchain and AI by offering a dynamic framework that adapts to technological advances while balancing growth and consumer protection.

As crypto technologies revolutionize financial systems through decentralized networks and digital assets, traditional regulatory frameworks often fall short. Policymakers can address this by reforming laws and regulations to incorporate the flexibility of regulatory sandboxes, the broad applicability of safe harbors, and the tailored clarity of no action letters. This integrated framework would support sustainable innovation, ensure regulatory clarity, and position the US as a global leader in the crypto and AI sectors. Finally, we’ll propose a blueprint “Sustainable Sandbox” for the crypto industry.

Roadmap:

I. What Are Regulations? How Are They Different from Laws?

a. Regulatory Sandboxes

b. No Action Letters

c. Safe Harbors

II. Regulatory Sandboxes in Practice

a. Common Issues with Regulatory Sandboxes

III. Designing the Ideal Sandbox

a. Our Recommendation for Redesigning the Sandbox for Digital Assets: The Sustainable Sandbox

b. How Our Sustainable Sandbox Would Align With “FIT 21”

c. Why There Is a Need for a Sustainable Sandbox Program Now

IV. Final Thoughts

V. ResourcesI. What Are Regulations? How Are They Different from Laws?

Let’s begin with understanding what regulations really are.

Congress passes a law and delegates authority to an agency to carry out that law, including by promulgating new rules (the regulations). Think of it as your boss who gives you a task but doesn’t tell you how to get it done—you have to figure it out. Same thing here. In general, the government uses three different approaches to regulate industries:

A command and control regulation is when the government dictates a specific policy goal and controls the way to achieve it (like a micromanager). For instance, in the context of vehicle safety standards, the government may dictate the exact dimensions of a testing dummy required to meet car testing safety requirements.

Performance-based regulation, on the other hand, is when the government sets a standard but allows flexibility in how to meet its standard. As an illustration, a regulation could set a car emission threshold for reducing CO2 emissions but not dictate the emission-reducing technology used to achieve that goal.

A management-based regulation is when the government sets a broad policy goal but allows the regulated entity to set its own standards and means to achieve that goal. For example, a regulation may require offshore drilling companies to develop a program designed to reduce environmental hazards like oil spills.

Despite what one may think, many legitimate (and particularly large) businesses generally like regulations because they reduce competition from new entrants. Indeed, becoming regulated is one of the oldest tricks in the book. By building a regulatory “moat” around a business model, regulated incumbents raise the cost of entry to their respective industries. While the main purposes of regulations are to create fair markets and protect the public, a key outcome is that not all businesses and activities are created equally, and you don’t want to regulate our startups and emerging companies and projects out of business.

Now, let’s explore the various tools the law has for regulatory innovation.

a. Regulatory Sandboxes

A regulatory sandbox is a framework set up by a regulatory authority that allows startups and other businesses to conduct live experiments in a controlled environment under the regulator’s supervision. Businesses apply to the sandbox to seek waivers for certain laws that, while technically applicable, may not align with their innovative activities. The goal is to enable experimentation with new products and services outside the strict confines of traditional regulations—without eliminating oversight..

Instead, the regulatory sandbox provides a controlled environment where businesses can collaborate with regulators to test their ideas, while still adhering to certain baseline standards to ensure consumer protection and financial stability. This collaboration allows both parties to identify which regulations may need to be adapted or clarified, balancing innovation with accountability.

A regulatory sandbox serves as a tool for identifying outdated regulations and accelerating innovation. By allowing businesses to test their ideas under controlled conditions, it ensures oversight remains in place to protect consumers. Entrepreneurs benefit from a regulatory waiver lasting two to three years, enabling them to innovate freely. In return, the sandbox generates critical data to assess whether the waived regulations should be reformed or repealed. Without such a mechanism, unnecessary or impractical regulations would remain in force, stifling progress and innovation.

The UK, along with several US states, have adopted financial technology sandboxes. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority’s Regulatory Sandbox has seen greater success, not just in participation but also in fostering innovation and collaboration, attracting a diverse range of entities, from large law firms to cryptocurrency projects, and enabling them to test new ideas within a structured regulatory framework.

b. No Action Letters

A no action letter is a written communication from a regulator to a company or individual who has asked the regulator whether a specific product or service implicates any regulations. If a company receives a no action letter, it’s an indication that the agency will not take enforcement action against the requester based on the facts described in a specific request. The letters are tailored to a very specific activity and may come with conditions.

While no action letters do not have the force of law and are not binding on the regulatory body, they can provide valuable guidance on regulatory compliance and are often used in areas of emerging business practices or where regulations may be ambiguous. However, they are also revocable at the discretion of the agency, which can leave a business scrambling to comply with an agency’s new regulatory stance. As an example, the state of California issued several no action letters concerning the registration requirements of cryptocurrency businesses that could have arguably qualified as money transmitters and thus been required to comply with burdensome regulatory requirements.

One recent letter described how a virtual currency exchange that purchases and sells virtual currencies directly with customers is not engaging in money transmission. With that no action letter in hand, the business could operate with a clearer understanding of its legal obligations and reduced risk of regulatory action. These letters, however, are very fact-specific, analyzing each discrete business model.

c. Safe Harbors

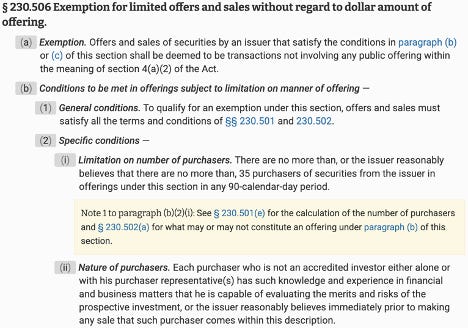

Lastly, a safe harbor is a law or regulation that states that if you perform certain actions, you are guaranteed not to be breaking the law. This is particularly useful in complex regulatory areas where the risk of non-compliance can be high and the rules may be open to interpretation. Unlike regulatory sandboxes, safe harbors are automatic (not needing an application and approval). Unlike no action letters, safe harbors have pre-defined criteria that must be met to qualify for the safe harbor.

One prominent safe harbor is Regulation D (“Reg D”), which establishes various requirements under which securities issuers can offer and sell securities without needing to register them with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”).

By adhering to these guidelines, issuers can ensure that they are in compliance with SEC regulations governing securities registration, protecting them from potential enforcement actions due to non-compliance. This safe harbor is especially important in the securities market because it provides a clear way for issuers to meet complex legal and regulatory expectations and reduce the significant risks of non-compliance.

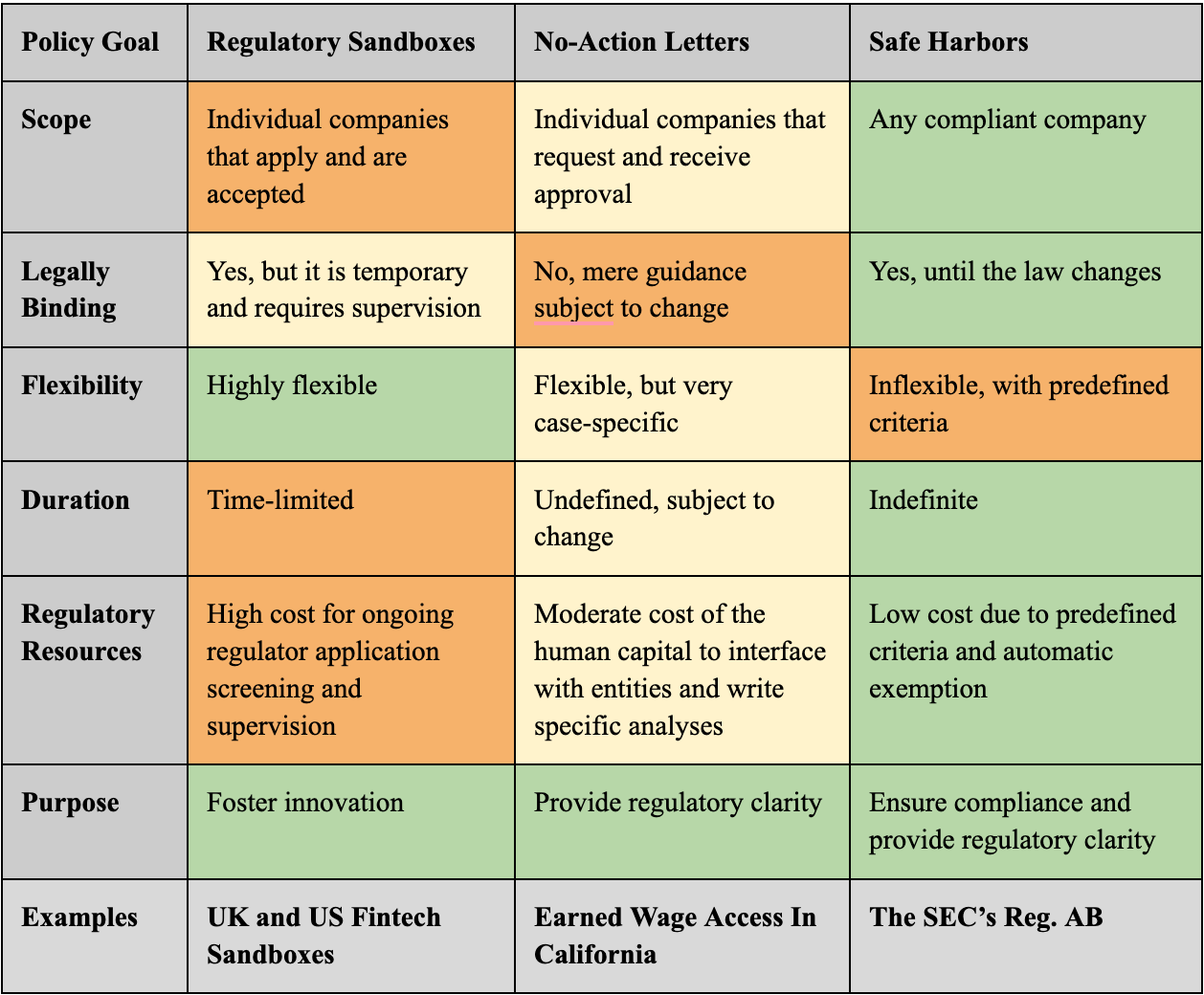

It’s important to note that these definitions can be fluid, and one tool for regulatory innovation can resemble another. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the design is more important than the terminology used to describe it. Rather, to design the ideal regulatory sandbox, one must take the best parts from these other policy tools.

II. Regulatory Sandboxes in Practice

While current regulatory sandboxes are specifically designed for regulatory innovation, they still lag behind no action letters and safe harbors in terms of efficacy and prevalence.

a. Common Issues with Regulatory Sandboxes

Several factors hinder the effective use of regulatory sandboxes, including a (1) narrow scope, (2) limited duration, and (3) high regulatory costs. However, these issues could actually be mitigated by incorporating elements from the safe harbors and no action letters.

(1) Scope: Regulatory sandboxes apply only to entities that meet strict conditions and are approved, unlike safe harbors, which automatically exempt all compliant entities. Adopting a more permissive model that would allow for more participants to enter the program, similar to safe harbors, could eliminate burdensome application processes and broaden accessibility.

(2) Duration: Regulatory sandboxes often have limited or uncertain timelines, requiring recertification. In contrast, safe harbors remain effective until enabling laws are amended. Regulatory sandboxes should offer longer or indefinite durations to provide businesses with greater stability and certainty.

(3) Cost: Regulatory sandboxes are resource-intensive for regulators, while safe harbors are cost-efficient, applying automatically without ongoing oversight. A streamlined, safe-harbor-like approach could significantly reduce costs.

In essence, the “ideal” regulatory sandbox should functionally resemble a more engaged safe harbor!

III. Designing the Ideal Regulatory Sandbox

Regulatory sandboxes are not common in the US. Admittedly, no federal regulator currently has a viable regulatory sandbox program for innovative industries, and the few state sandboxes are still not fit for sustainable regulatory innovation, especially in the digital assets industry.

We propose a new “Sustainable Sandbox” for the crypto industry that fast-tracks supervised innovation of digital assets.

a. Our Recommendation for Redesigning the Sandbox for Digital Assets: The “Sustainable Sandbox”

Let’s roll up our sleeves and dive into the practical work of designing the ideal regulatory sandbox. This enhanced regulatory sandbox, a “Sustainable Sandbox,” should integrate the best features of existing frameworks while significantly adapting to the dynamic nature of the cryptocurrency sector.

Phase 1: Sandbox Enrollment

Simplified Automatic Enrollment: Registration for sandbox participation should be streamlined to a simplified checkbox form. The focus should be on fulfilling the basic requirements in the form and basic compliance (e.g., appointment of a chief compliance officer) rather than substantive evaluation of the underlying business model or technology.

Management-Based Approach to Design: For businesses that don’t fit the traditional compliance structures in the checkbox form—such as decentralized exchanges or decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs)—an alternative management-based approach would allow participants to develop their own compliance frameworks. Regulators should set broad policy goals, such as transparency or fraud prevention, and participants can then propose their own standards and methods to meet those goals, subject to regulatory approval. This flexibility accommodates innovative and decentralized models while ensuring oversight. By focusing on outcomes and collaborating with industry stakeholders, regulators can address technological knowledge gaps while promoting effective compliance.

Phase 2: Sandbox Oversight

Exemption During the Sandbox Period: To encourage participation and avoid deterring projects, participants should operate under a presumption of exemption from certain regulations, allowing them to innovate without the burden of potentially inapplicable laws. Clear guidelines upfront can alleviate concerns, though this exemption should not preclude enforcement of fraud or UDAP/UDAAP claims (i.e. unfair, deceptive or abusive business practices that harm consumers), ensuring protections against deceptive practices remain intact.

Annual Reporting for Ongoing Oversight: Participants should be required to submit annual reports detailing specific operational aspects, such as cybersecurity incidents. This will ensure ongoing oversight and responsiveness to emerging risks without stifling innovation. It also allows for the collection of metrics to measure the effectiveness of the sandbox.

Phase 3: Sandbox Exit

Transition to a Safe Harbor: The regulator in charge of the sandbox should, if it is able to, use the information the sandbox provides to create a tailored, sensible safe harbor once the sandbox ends. This would provide a stable, long-term framework for continued operations while ensuring compliance with the newly established rules.

Issuance of No-Action Letters as a Contingency: If the regulatory framework remains uncertain at the end of the sandbox, participants should alternatively be issued no-action letters. These letters would provide assurance that the regulator will not pursue enforcement actions against entities that continue operations under the terms established during the sandbox. This approach offers a more permanent and predictable pathway for participants, making the initial investment in the sandbox worthwhile.

By adopting these parameters, the next US crypto regulatory sandbox could serve as a powerful tool for fostering innovation and growth in the cryptocurrency sector. This approach would align regulatory frameworks with the rapid pace of technological advancements, ensuring that the US remains at the forefront of the crypto industry while maintaining robust consumer and market protections.

b. How Our Sustainable Sandbox Would Align With “FIT 21”

The Sustainable Sandbox offers a pathway to address one of the most contentious debates in blockchain regulation: defining and measuring decentralization. Decentralization, a cornerstone of blockchain technology, promises enhanced security and privacy through distributed networks, but its regulation has proven divisive. The decentralization test outlined in the current draft of the Financial Industry Transparency for the 21st Century Act (“FIT 21”)–the leading legislative proposal aiming to regulate much of the crypto industry–has sparked widespread debate within the sector over what truly constitutes decentralization and how it should be regulated. This discord among industry players poses a significant challenge: if the crypto industry itself struggles to reach a consensus, how can lawmakers be expected to create effective regulations? That’s where the “Sustainable Sandbox” comes into play.

The Sustainable Sandbox would act as a bridge between innovation and regulation, offering a structured environment to address the decentralization debate while fostering experimentation and data-driven policymaking. Participants in the regulatory sandbox would be able to test their models of decentralization under real-world conditions without the fear of immediate regulatory enforcement. This would allow both the industry and regulators to collaboratively identify practical frameworks that balance innovation with compliance. Participants would gain the opportunity to refine their decentralized technologies while providing regulators with data-driven insights.

The Sustainable Sandbox would use a management-based approach to ensure flexibility and inclusivity for a wide range of participants. While a standard check-box filing system might suit many businesses, the management-based model would accommodate more innovative or decentralized entities that fall outside traditional regulatory frameworks. For example, a decentralized exchange without a conventional corporate structure—such as a c-suite or chief compliance officer—would not align well with standard regulatory processes. Instead, the management-based approach would allow the regulatory sandbox regulator to set high-level policy goals, like promoting transparency, mitigating risks, and ensuring consumer protections, while participants design their own standards and methods to achieve these objectives, subject to regulatory review and approval.

This approach ensures that the regulatory sandbox supports diverse business models, particularly those leveraging decentralized technologies, while maintaining oversight aligned with broader policy objectives. The Sustainable Sandbox would serve as an experimental platform to:

Define and Measure Decentralization: Develop clear, industry-supported metrics that define what decentralization means in various contexts within the crypto space. This includes tailoring distinct tests to assess decentralization across different market participants, ensuring that the criteria are relevant and appropriately stringent for each sector, whether they be layer 1s, applications, or DAOs.

Assess Regulatory Fit: Evaluate how different levels of decentralization interact with existing legal frameworks to determine if adjustments are necessary.

Influence Policy Development: Provide lawmakers with concrete data and insights into how decentralized technologies operate, supporting more informed legislation and regulation.

By adopting this management-based approach, the Sustainable Sandbox creates a thoughtful and iterative pathway to regulation, avoiding rushed or premature decentralization frameworks that could harm innovation or market stability. It ensures that both regulators and the industry are equipped to address the evolving challenges of decentralization and digital asset innovation.

In the dynamic landscape of blockchain and cryptocurrency, the importance of regulatory timing cannot be overstated. As we face the prospect of new administrations potentially reshaping the regulatory environment, there is a significant opportunity to influence the trajectory of policy development. However, this window should not compel us to rush into premature regulatory frameworks that could have long-term negative impacts on innovation and market stability.

c. Why There Is a Need for a Sustainable Sandbox Program Now

The need for regulatory innovation stems from two incentives: a “carrot” for businesses and a “stick” for regulators.

Innovative industries like blockchain and AI struggle with outdated legal frameworks that fail to address novel challenges. These industries seek regulatory certainty—a “carrot” that fosters innovation and compliance by providing clear rules. Tools like the Sustainable Sandbox allow companies to grow within legal boundaries while building accountability and trust. At the state level, stringent agreements with regulators show how structured frameworks can balance innovation and oversight.

Meanwhile, regulators face a “stick” from the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024) (see prior article), which limits courts' deference to agencies’ interpretations of their own authority. This decision shifts power toward highly regulated industries, granting them greater influence over how they are governed. Courts now independently assess an agency’s authority, reducing reliance on agency interpretations.

The power shift between agencies and industry requires agencies to adjust their practices and creates opportunities for more collaborative governance between agencies and industries. The Sustainable Sandbox is ideal for this task. Now is the time to implement the Sustainable Sandbox collaboratively, adapting to the new regulatory landscape.

IV. Final Thoughts

As technology advances, regulations must evolve to keep pace. Sandboxed environments provide controlled spaces for regulators to test ideas, gather data, and refine governance strategies for new technologies. Our Sustainable Sandbox proposal a forward-thinking framework, resilient to rapid innovation and designed to adapt alongside technological progress.

[Special thanks to Bryan Edelman, Jane Perov, Sam Reynolds, and Sam Silverberg.]

V. Resources

Joshua Durham, REGULATORY SANDBOXES ENABLE PRAGMATIC BLOCKCHAIN REGULATION, 18 Wash. J. L. Tech. & Arts (2023) - available at https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wjlta/vol18/iss1/3

https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/a-few-thoughts-on-regulatory-sandboxes/

https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/psd/four-years-and-counting-what-weve-learned-regulatory-sandboxes

https://www.theregreview.org/2016/04/05/pritchett-types-of-regulation/

https://financialservices.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=409277

https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/speeches-statements/peirce-boe-fca-comment-05302024

https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/speeches-statements/peirce-statement-token-safe-harbor-proposal-20

See generally 49 CFR Part 572.

See generally 30 CFR Part 250 Subpart S.

Images: All original images are AI-generated with using a combination of Dall-E, Firefly, DreamStudio and Pixlr.

Disclaimer: This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. This post reflects the current opinions of the author(s) only. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.