Read the Fine Print: Token Compensation

What You Need to Know About Your Token Package When Working With a Crypto Startup

[This article was originally published on Dragonfly’s Blog and is co-written with Brandon Ferrick. This is a follow up piece to a prior post on understanding stock options.]

For employees, consultants, and advisors at crypto startups, understanding token compensation is just as critical as understanding equity. Tokens may look deceptively simple—digital units recorded on a blockchain—but in practice, they come with their own thicket of legal, tax, and liquidity issues. Unlike equity, which has decades of case law and established market norms behind it, token compensation sits in a fast-evolving, often ambiguous regulatory environment.

This article is designed to demystify how token packages are structured, when and how tokens are actually delivered, and the restrictions and risks that may come with them. Whether you’re reviewing a consulting agreement, joining as an early employee, or advising a project in exchange for tokens, it pays (literally) to know what you’re signing up for.

The article is written with a focus on U.S. audiences, so for non-U.S. service providers, make sure you consult local tax and legal professionals for jurisdiction specific matters. Either way, we are lawyers but not YOUR lawyer, and this isn’t legal advice.

Note, be sure to read the glossary at the bottom of the document for important definitions and concepts described here.

Roadmap

I. What Are Tokens?

A. Software Is Not Equity

B. Dual Track Compensation

C. Paperwork

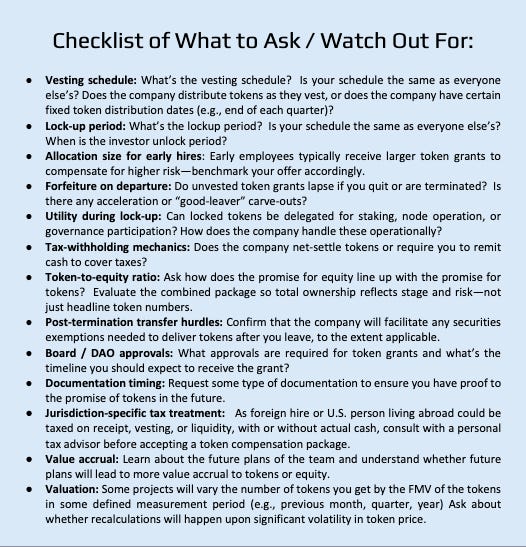

Checklist of What to Ask / Watch Out For

II. Types of Token Incentive Compensation

A. Restricted Tokens or Restricted Token Awards (RTAs)

B. Restricted Token Units (RTUs)

III. Differences Between Token v. Equity Comp

A. No 409A safe harbor

B. It bears repeating: tokens are not equity

C. Tokens are pseudonymous

D. Tokens can be more liquid than stock options

E. Tokens are taxed the same as stock (for the most part)

F. You may be granted a token interest or a token

G. Paperwork may be delayed

H. Tokens are subject to lockups and vesting (different restrictions)

I. Transfer restrictions enforced via smart contracts or custodians

J. Typical timelines for lockups and vesting schedules

K. Acceleration for tokens

L. Withholding taxes / net settlement

M. You may not be able to participate in governance until you vest

IV. Tips and Nuances

A. How to Value What You Are Getting

B. What Happens If You Leave the Company?

C. What If I’m a Non-US Person?

V. Glossary of Key Terms

VI. Sources

I. What Are Tokens?

A. Software Is Not Equity

Tokens are units recorded on a blockchain that can enable access to or voting power of a protocol. Critically, tokens are (usually) not equity and usually do not resemble traditional securities.1 Because of that, they confer no shareholder rights—no dividends, no corporate voting2, no residual claim on company assets. In other words, you should never confuse token ownership with owning stock. That said, it’s important to read the rest of this article to understand where tokens function like stock and where they differ, so you can evaluate what receiving or selling tokens may mean for you and conduct appropriate due diligence before accepting tokens as compensation.

B. Dual Track Compensation

In Web3, companies may issue tokens to their service providers in addition to, or in lieu of, equity. This is because in Web3, value may accrue to a decentralized, token-governed system rather than to the equity in a development company (DevCo). For more information about market trends in offers, we recommend Dragonfly’s 2024/2025 Crypto Compensation Report.

That said, token-based awards often (but not always) track the structure of traditional stock awards made under equity compensation plans, as a company will adopt a token plan along with individual form agreements. This was born out of a combination of not wanting to reinvent the wheel on incentive compensation, as well as an effort for companies to comply with existing securities laws during periods of high regulatory uncertainty.

C. Paperwork

As mentioned above, just like many companies have equity incentive plans/stock incentive plans, crypto startups often create token incentive plans whereby they’ll award tokens to the company’s service providers, as a form of incentive compensation—the most common papered forms of token awards are papered are the following:

Restricted Token Awards (RTAs) and

Restricted Token Units (RTUs)

[Note: We won’t go into token options and Token Purchase Agreements (TPAs) in this primer. Token options are pretty rare. TPAs are effectively the same as RTAs except that TPAs are paid for with cash while RTAs can be paid in either cash or services.]

II. Types of Token Incentive Compensation

Now, let’s get into the nitty gritty of RTUs and RTAs.

A. Restricted Tokens or Restricted Token Awards (RTAs)

1. What is it?

These are actual tokens issued to service providers, subject to some vesting restrictions (e.g., if you stop providing services to the company before they vest). You own these tokens and generally pay taxes in the year you receive them. The company’s right to take back the tokens (usually repurchase them upon separation) lapses as they vest. Unvested tokens are typically also subject to restrictions on transfer (but can be adjusted for estate planning purposes).

2. When do you see an RTA used?

When the fair market value of the token is still very low, usually pre-TGE, before a funding round has attributed a market-driven valuation to the tokens (i.e., before any SAFTs, token subscriptions, or token purchase agreements are entered into). So, you tend to see this used for grants issued after tokens have been minted but prior to a token being publicly launched.

3. When does settlement happen?

Title transfer happens around the time of the award for these. You need to give the team member title to the tokens, subject to the repurchase right. This means either actually give the tokens to the employee, or transfer legal title to them via legal agreement and have the company or a custodian hold them on behalf of the team member until vesting. Delivery of the tokens themselves may take place over time as vesting occurs after the lockup and cliff expires, sometimes using a platform such as Liquifi or Magna. There’s a bit of a debate over whether a multisig / smart contract vesting schedule is sufficient for 83(b) purposes where the employee doesn’t have dominion and control over the asset.

4. How are they taxed?

Token compensation is taxed as ordinary income at the time of grant. As with equity, you would generally be granted an RTA for unvested tokens, to incentivize you to earn them over a period of time with your contributions. If so, taxes can work in one of two ways, depending on whether you file an 83(b) election:

No 83(b) Election: If you don’t file, you are taxed when the tokens vest so you have to pay ordinary income on the value of the tokens at each vesting milestone. It can be costly if the token price appreciates. Since you likely can’t sell the tokens during the lockup, you could be stuck with a large tax bill and no liquidity to pay it!

83(b) Election: If you file one within 30 days of the transfer, you pay ordinary income at the time of grant on the fair market value of the entire grant, vested or unvested. The token hopefully is worth more over time, so it makes sense to pay taxes on the full grant value at the time of the grant, rather than taxes at each vesting event for the amount of tokens that vested. Once you go to sell the tokens, depending on how long you hold them, you can be taxed at the capital gains rate.

Note: Tokens need to be minted and issued to the employee or service provider, as 83(b) elections can only be made on property you receive. Some firms may take a different perspective on this, so make sure you consult with a tax professional before accepting any tokens and filing an 83(b) election.

For RTAs, you technically own all of the tokens at grant under reverse vesting. However, the company retains the contractual right to repurchase any unvested tokens for a nominal amount if you leave before they vest. This “substantial risk of forfeiture” is what drives the default tax rule—without an 83(b) election, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) treats the taxable event as occurring at vesting, not grant. Filing an 83(b) lets you accelerate the tax recognition based on the grant date despite this forfeiture risk.

Let’s say you were granted an RTA for fully vested tokens, then no 83(b) would be necessary and you would have a tax consequence on all the tokens under the RTA upfront.

5. Are there transfer restrictions?

Yes, through vesting and lock-ups.

6. How do you pay for it?

RTAs can be either purchased or received as compensation for services.

B. Restricted Token Units (RTUs)

1. What is it?

An RTU is akin to a restricted stock unit (RSU) in that an RTU is not an actual token but rather a contractual obligation to transfer tokens to the service provider in the future. You are issued tokens at the point of vesting. One unit is equal to one token.

2. When do you see an RTU used?

If the fair market value of the tokens would result in a material tax burden (i.e., if it would be too expensive for the contributors to make an 83(b) election because you have to pay taxes on the full value upfront), then that’s when you use RTUs. RTUs are most often used after a token is launched and in circulation (recall, most U.S. employees, consultants and advisors take RTAs pre-launch).

3. When does settlement happen?

Once the tokens vest, they will be delivered to the service provider’s wallet, but there could still be a transfer restriction via the unlock if the dates for the unlock and the vesting don’t align.

4. How are they taxed?

Service providers are taxed at settlement (i.e., delivery ), not when the RTUs are granted. With RTUs, you do not own the tokens until they settle in your wallet. Hence, there’s no option for an 83(b) election as there’s no property to elect on. The taxable amount is based on the fair market value at settlement, which also becomes your cost basis for future sales. Tokens are often issued on a net basis, meaning the company will sell a portion of your tokens to satisfy the taxes for each settlement date. There may be an option to structure it as deferred compensation and defer tax recognition, so it’s worth asking if that’s an option.

5. Are there transfer restrictions?

Yes, through vesting and lock-ups.

6. How do you pay for it?

Not really, you just earn them from working, which is why you pay taxes when you receive them.

III. Differences between Token v. Equity Comp

A. No 409A safe harbor.

Like equity, a token is valued for tax purposes by an independent, third-party valuation (from companies like Redwood or Teknos). In the equity context, people often refer to an independent valuation as a “409A Valuation” after Section 409A of the Internal Revenue Code, but while 409A Valuations last for up to 1 year, token valuations may go stale after 1 to 6 months – depending on the specific valuation company’s methodology and life cycle of the underlying company or token ecosystem. Unlike equity compensation, tokens probably don’t qualify as “service recipient stock” under Section 409A (meaning they probably aren’t treated like common stock by the IRS).

B. It bears repeating: tokens are not equity.

We may be wading into political territory here now, but objectively worth the risk. Here are a few reasons why:

Stock represents ownership of a company, and ownership means you have rights under the law as a shareholder (like the right to inspect the books, claim to the company’s assets, receive dividends, vote for major company decisions, etc.). Companies often have a board of directors who have a fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value.

Tokens aren’t meant to bestow ownership of the company itself, so you aren’t entitled to any of those shareholder rights mentioned above. Rather, tokens are meant to support the development of and participation in a decentralized protocol (which is autonomous software, not a company). Protocols don’t have boards of managers who are obligated by law to maximize token value. In fact, public pronouncements by companies that they will dedicate themselves to maximizing token values may inadvertently trigger securities laws in certain jurisdictions. There are different types of tokens (utility, governance, security, etc.) and each token may offer some but not all of the following functions: access to services on the protocol, voting rights toward design of the protocol, etc. These are functions determined by innate, programmatic features of the underlying protocol, not legal prescriptions. Additionally, tokens can often be sold on public exchanges sooner than stock options, giving them an advantage in liquidity once restrictions are lifted.

C. Tokens are pseudonymous.

While stock ledgers track the name of a person or entity, token transactions on blockchain networks are typically linked to cryptographic addresses rather than real-world identities. This means that, unless specifically associated with an individual through Know Your Customer (KYC) processes or other off-chain methods, the identity of a token holder remains hidden.

D. Tokens can be more liquid than stock options.

The vast majority of startups fail, with over 95% failing in the 90’s and closer to 80% failing these days. So, unless there is an IPO, M&A deal or a company buy-back/tender offer, your options to purchase stock may be worth nothing at the end of the day, and due to transfer restrictions and limited ways to find a buyer, you may never have the opportunity to sell your shares and make money. Tokens, on the other hand, can be sold on public exchanges (decentralized or centralized) once they launch and any applicable restrictions are lifted.

E. Tokens are taxed the same as stock (for the most part).

Whether you get a bonus in stock or a bonus in tokens, both will be taxed (in the U.S.) as ordinary income upon receipt—the IRS treats the bonus as a receipt of property. After that point the token is generally viewed as a capital asset in the hands of the taxpayer (so capital gains treatment on disposition if you hold it for over a year). Similarly, whenever you get around to selling your shares (or tokens) you will be taxed based on the prevailing capital gains rate, as both are considered (usually) to be capital assets in your hands. That said, tokens are not eligible for qualified small business stock (QSBS) preferred tax treatment, so make sure you speak with a professional accounting advisor to understand your potential tax liability.

F. You may be granted a token interest or a token.

You may be granted either tokens outright or a right to receive tokens in the future. If you are issued tokens immediately, this functions much like a stock grant, and you may have the option to file an 83(b) election to accelerate taxation to the grant date. If you are instead only receiving a right to tokens later—typically tied to vesting or a network launch—you do not yet own tokens. In that case, the arrangement is more like an RSU: a contractual right that settles into actual tokens once the vesting or release conditions are met. If you are granted a token interest for unvested tokens, check with your tax advisor to see when it makes sense for you to file an 83(b).

G. Paperwork may be delayed.

Don’t be surprised, however, if your company doesn’t have a formalized token incentive plan: many companies believe that since their tokens are not regulated as securities, they can take the least operationally-intensive path forward, and give tokens directly to their team without robust token plan documentation. The existence or lack of an incentive plan shouldn’t be viewed negatively when you’re evaluating whether to accept a company’s tokens as part of your compensation, but you should inquire why the team chose one direction over another.

In many cases, a company will start solely by issuing equity to the team and later, once the company’s product is developed, they’ll create a token and issue some of it to their service providers. So, it’s possible you may start a gig at a company and not get any tokens until a point in the distant future, but your offer letter or service agreement may make an explicit promise of tokens if, and only if, tokens are ever created. Although, there is often no agreement nor specific promise, but rather just a handshake. What’s important to understand is that you are unlikely to ever see any sort of value associated with any token promises, as promising tokens with any kind of value pre-launch will likely cause tax risks (not tax advice).

Because token launches are complex and take many forms, you may not see any formal agreements until after the tokens are minted.3 That’s why the offer letter is very important as it may be the only document that serves as proof of a right to the token. It’s important to have an offer letter that outlines the comp structure and conditions.

H. Tokens are subject to lockups and vesting, which are 2 different types of transfer restrictions.

People often confuse lockups with vesting or use these terms interchangeably. Lockups refer to restrictions on transferability whereas vesting refers to whether or not the service provider has shed the risk of forfeiting or losing the tokens by satisfying the conditions imposed at the time of the token award. Both prevent you from being able to own the tokens “free4 and clear” of any restrictions.

Lockup refers to the period of time during which tokens cannot be sold or transferred. In many cases, the company maintains administrative custody of the tokens until they unlock.

Vesting refers to either the removal or lapsing of the company’s right to take back your tokens or the accrual of your rights to receive them. Unvested tokens, like unvested stock, are usually forfeited or repurchased upon termination of the individual’s service relationship with the company.

Once the token unlocks and is fully vested, the service provider has full control and ownership of the tokens underlying the token award in question and may hold or transfer/dispose of the tokens as they see fit. (But keep in mind you may have to pay taxes when you sell the tokens based on the difference between your basis in the tokens and fair market value when you sell them!)]

I. Transfer restrictions are enforced via smart contracts or custodians.

Transfer restrictions for tokens can refer to both the vesting and lockup (usually by mistake, when people are just speaking in shorthand). Typically, token agreements specify that tokens cannot be transferred until the later of when the vesting or lockup period is complete, partly because there could be a liquidity mismatch in non-83(b) scenarios. What do we mean by this? Since taxable income generally arises upon vesting, recipients without an 83(b) election may owe tax before they’re able to liquidate tokens. If a lockup is still in effect at vesting, this creates a liquidity mismatch that precludes sell-to-cover strategies (i.e., selling some tokens to cover your taxes). Once both conditions are met, the contributor can transfer their tokens to personal wallets or directly from company-controlled wallets. While your tokens remain subject to transfer restrictions, typically a third-party service provider (ex: Coinbase) will prevent you from transferring your tokens until the transfer restrictions lapse.

J. Typical timelines for lockups and vesting schedules.

The unlock / vesting schedules commonly do not track identically. Employee tokens are typically subject to a 4-year vesting period (but we have seen three years with some increase in popularity in recent years). The vesting schedule usually starts from your first day as an employee. If you receive tokens a few years after you join a company, the company will commonly give you vesting credit for your service to date. Often there’s a 1-year cliff (i.e., you have to wait 1 year to get a large chunk (25%) of the tokens), and the remaining will vest monthly over the remaining 3 years. Lockups tend to vary from 1 (in the case of liquidity providers, or other non-personnel ecosystem participants) to 4 years (for everyone else) in total, with the first tokens unlocking 1 year after the issuance of tokens or token launch.

Employees are typically subject to the same unlock schedule as all insiders (i.e. founders and investors). The 1-year cliff for lockup is done for securities law purposes (sometimes you’ll see 6 months for employees outside the US); in case tokens are deemed securities, then you need to have a holding period before the tokens could be sold to comply with securities laws. It can also be used to build confidence among a community of token holders: if employees/founders are able to sell quickly, the community may not have confidence that they’ll actually execute and just see it as a money grab. Lockups usually commence as of the TGE date, so depending on whether the token is live, the lockup and vesting start dates may not be the same. If the token launch has occurred, then the lockup probably begins when granted, and if prior to the token launch, it will begin at the token launch.

For consultants and advisors, you can expect a similar vesting and lockup duration. The only exception would be where you anticipate your relationship with the company to be shorter than 3 or 4 years, in which case vesting might be on an accelerated timeline (e.g., 1 year) but lockups would likely stay the same length as everyone else’s (particularly for a pre-launched token). If you’re only providing services for a few months or a year and are being offered tokens, be sure to ask for a vesting schedule that is commensurate to the amount of time you’ll be supporting the company.

K. Acceleration for tokens.

Recall that acceleration refers to the early vesting of equity upon certain events—usually a sale of the company or termination of employment. Double-trigger acceleration (DTA) (sale and termination) is more common and palatable to investors, while single-trigger acceleration (STA) (just the sale) is harder to get and often resisted; still, it’s worth asking for, especially if you are a key employee.

In the token space, DTA or STA are uncommon because there’s generally no change of control event that would interfere with token accrual rights; however, token accelerations upon termination do sometimes occur, though they’re typically not offered upfront and are instead provided as consideration for signing a separation agreement.

L. Withholding taxes are also a thing.

Tokens paid as compensation (as part of base compensation or bonuses) are subject to federal and state withholding taxes (employers can be secondarily liable for such taxes and face penalties if not paid). For RTUs, the project can either use net settlement, where tokens are withheld to cover taxes, or cash settlement, where the service provider receives all tokens and is responsible for paying the tax liability in cash by remitting cash back to the company equal to their tax obligation. Technically, the prior sentence could work for RTAs too, although in practice contributors almost always make 83(b) filings for RTAs and pay taxes upon issuance.

M. You may not be able to participate in governance until you vest.

As a stockholder, you can vote your shares whether vested or unvested (though not options or RSUs). Whether you can vote your unvested tokens depends on who possesses them. You may not be able to participate in governance with unvested tokens unless the tokens are in a wallet you control, or the company facilitates it. If you receive tokens under an RTA but the company continues to possess them pending vesting, you likely won’t be able to use those tokens to vote in governance.

IV. Tips and Nuances?

A. How to value what you are getting

With equity compensation, a company might promise you 0.3% of the fully diluted shares of the company. Similarly, token allocations are sometimes tied to your equity ownership percentage in the company given that it’s difficult to promise an exact number of tokens since companies often don’t know the total size of their token network at the time of grant. Sometimes, you may be allocated a fixed number of tokens pre-TGE, but that would usually be the case after the company knows the total supply and can vary depending on how close the company is to its token launch. Often, your ownership percentage of the token network will be based on a percentage of the company reserve (portion of the network reserved for insiders), rather than a percentage of the entire token network. Recently, we’ve been seeing a lot of companies use fair market value calculations when giving grants, calculated based on time- or volume-weighted averages.

Whether offered a hard number or percentage, that offer will likely look something like this:

Subject to Board approval and the creation of the anticipated cryptocurrency network, the company anticipates granting to you an award of tokens with the right to receive:

[your pro-rata share of the company’s token reserve native to such cryptocurrency network (based on your fully-diluted equity holdings in the company at the time of the Network Generation)] OR

[[_____] tokens native to such cryptocurrency network]

If you are receiving a hard number, you might want to ask what percentage of the fully diluted equity it represents so you have context. If the token is minted, but not publicly launched (i.e. you can’t see what it’s trading at), it’s fair to ask what the valuation is at the time you’ll be granted it.

If the token hasn’t been minted yet, consider looking at comparable protocols or networks to see how their value has grown or shrunk over time.

B. What happens if you leave the company?

If you leave or stop providing services to a company prior to the token launch, there is a risk that because there is no contractual obligation to issue your tokens, the company may not do so once the token is minted. Also, even if the company is willing to still issue your tokens, you may need to qualify for another securities law exemption that differs from what active service providers can rely on. Good to have a conversation with your company if you plan to leave about how they will do right by you, and get that in writing!

If you leave the company and your tokens are only partially vested and partially unlocked, the company has a right to repurchase any RTAs that are unvested usually for a nominal value. For RTAs, if an 83(b) election is made and unvested tokens are forfeited, the taxes paid upfront are generally non-refundable. For RTUs, the unvested portion simply wouldn’t settle to your wallet.

C. What if I’m a non-U.S. person?

RTAs and TPAs are primarily for U.S. service providers due to specific tax elections available in the U.S. and UK, like the 83(b) election, which allows tax payments at the time of award rather than vesting. Outside the U.S. and U.K., RTAs and TPAs don’t offer the same tax advantages. Service providers in other regions generally use RTUs, which don’t allow the same tax optimizations as RTAs and TPAs. If you are a non-U.S. person who plans to become a U.S. tax-resident during the vesting period, you may want to file an 83(b) anyway.

For non-U.S. persons, token grants can be taxed very differently depending on jurisdiction — potentially at receipt, vesting, or sale, and sometimes regardless of liquidity. In some countries, employer withholding rules may apply or treaty relief may be available. Generally, tokens paid to non-employee service providers don’t require a company to withhold tax (there’s no withholding on consultants or advisors). Recipients should confirm local tax treatment before accepting tokens, especially if they are mobile employees or may relocate during the vesting period.

V. Glossary of Key Terms

83(b) Election: Under the Internal Revenue Code, recipients of property can elect to be taxed at the time they receive the property—on the spread between fair market value and purchase price—rather than at vesting. For token grants, eligibility for an 83(b) election (or equivalent in other jurisdictions) may determine the form of award issued, due to differing tax treatment.

Acceleration: Acceleration means your vesting happens faster than originally planned. This can occur under certain conditions, such as the sale of the company (a “change of control”) or if you’re terminated without cause. For example, “double-trigger acceleration” requires both a sale and termination to accelerate vesting, while “single-trigger acceleration” requires only one of those events.

Capital Gains vs. Ordinary Income: When you first receive or vest in tokens, their value is generally taxed as ordinary income—like a paycheck. Later, when you sell those tokens, any increase (or decrease) in value is treated as a capital gain (or loss). The rate you pay depends on how long you held the tokens: gains on tokens held more than a year usually qualify for lower, long-term capital gains tax rates.

Cliff: The cliff is the initial period before any of your tokens start to vest. For example, if you have a one-year cliff on a four-year vesting schedule, none of your tokens vest until you’ve completed one full year of service—at which point a chunk (often 25%) vests all at once. After that, vesting typically continues monthly or quarterly.

Custodians: It’s become more common for companies to use custodians instead of smart contracts for token compensation. A company will set up a qualified custodian/wallet for each contributor and use services like Coinbase Institutional, Copper Custody, LiquiFi, Magna, or Toku to manage vesting and lockup.

DevCo (Development Company): The Development Company or DevCo is the traditional legal entity—often a corporation or limited company—that builds and maintains the decentralized project or protocol. It’s separate from the decentralized network itself, which may be governed by token holders or a DAO.

Governance Rights: Governance rights to tokens enable holders to participate in decision-making processes on the blockchain, such as voting on protocol updates or network changes. These rights may be restricted until tokens vest or lock-ups expire. Companies may build in restrictions on service provider governance rights into the token comp paperwork and the smart contract.

Lockup: A lockup is a set period of time when you’re not allowed to sell or transfer your tokens. During this period, the company often holds the tokens programmatically for you until they “unlock.”

Minting: This is the process of creating new tokens and first circulating them on a blockchain.

Smart Contract: Think of a smart contract as software code that automatically executes whenever certain conditions exist. Like a vending machine, if you put a dollar into it and select a beverage, the machine knows to release that specific drink. Using the word “contract” is a bit of a misnomer. It’s not a legal contract per se, but the idea is that it enforces the terms written into the code without needing intermediaries.

In the context of token compensation, companies may use smart contracts to automate the vesting and unlock of tokens. The smart contract in this example will hold the tokens in escrow until they are released once vesting/unlock milestones occur.

Settlement: This refers to when tokens are delivered to the participant upon meeting certain conditions. Some companies bifurcate vesting and settlement events for administrative ease. E.g., you may vest on May 12th, but the company may do monthly token deliveries on the last day of each month or quarter.

Token Generation Event (TGE): The event in which tokens are created or “minted” by the company. For tokens that are not yet live, service providers generally receive tokens shortly after the TGE, which can be subject to vesting and lock-up periods.

Token Launch: This is the date when tokens are first sold to non-insiders (i.e., service providers and existing company investors). Service provider lockups are commonly measured from the Token Launch rather than from the date of issuance.

Vesting: Vesting is about earning the right to fully own your tokens. It means the company can no longer take them back once you’ve met certain conditions—like staying with the company for a set time or achieving specific milestones. Unvested tokens, like unvested stock, are usually forfeited or repurchased if you leave before they vest.

Withholding / Net Settlement: When tokens are treated as taxable compensation, the company may need to withhold taxes. In a net settlement, the company keeps or sells a portion of your tokens to cover the tax amount before transferring the rest to you. Alternatively, you might be required to pay the taxes in cash.

* * *

Token comp is still pretty new so the landscape is constantly evolving so make sure to seek out advice from a competent lawyer and/or tax professional.

Good luck!

Special thanks to the following people who reviewed this article in their individual capacities: Chris Ahsing, Jordan Blum, Bryan Edelman, Jonathan Edwards, Benjamin Helfman, Lindsay Lin, Nima Maleki, David Safren, Lee Schneider, Darin See, Zack Skelly, Demetrios Stellatos and Connor Tweardy

VI. Sources:

26 U.S.C. § 409A

26 CFR § 1.409A-1

Digital assets, Internal Revenue Serv., https://www.irs.gov/filing/digital-assets

Darren Goodman, Taryn E. Cannataro, & Jessica I. Kriegsfeld, Taxation of Token Awards: What You Should Know, Lowenstein Sandler LLP (Mar. 2024), https://www.lowenstein.com/news-insights/publications/articles/taxation-of-token-awards-what-you-should-know-goodman-cannataro-kriegsfeld

Ethan Lippman, Navigating the Dual Equity Paradigm: Stocks vs. Tokens, Medium (Jul. 29, 2023), https://medium.com/ethsign/navigating-the-dual-equity-paradigm-stocks-vs-tokens-8733c6414bea

Guangye Cao, Startup Financing: Token vs Equity, University of Michigan (Aug. 2023), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.04662

Jake Chervinsky & Jesse Walden, Tokens Versus Equity, Variant (June 26, 2025), https://blog.variant.fund/tokens-versus-equity

Josh Howarth, Startup Failure Rate Statistics (2025), ExplodingTopics (June 5, 2025), https://explodingtopics.com/blog/startup-failure-stats

Kyril Kotashev, Startup Failure Rate: How Many Startups Fail and Why in 2025?, Failory (July 31, 2025), https://www.failory.com/blog/startup-failure-rate

Madan Nagaldinne, Craig Naylor, & Mehdi Hasan, How tokens can attract top talent: A compensation primer for web3, a16z crypto (Aug. 8, 2024), https://a16zcrypto.com/posts/article/token-compensation-guide/

Martin Lipton, Cryptocurrency Compensation: A Primer on Token-Based Awards, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (May 19, 2018), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/

Matthew Bartus, What is a Section 83(b) Election and Why Should You File One?, Cooley GO (July 14, 2025), https://www.cooleygo.com/what-is-a-section-83b-election/

Minting, Ledger Academy (June 10, 2023), https://www.ledger.com/academy/glossary/minting

Practical Law Employee Benefits & Executive Compensation Team, Expert Q&A on Cryptocurrency Compensation, Practical Law (Nov. 10, 2022), https://www.cooley.com/-/media/cooley/pdf/expert-qanda-on-cryptocurrency-compensation.pdf

Robert Delgado, Erinn Madden, Carly Rhodes, & Washington National Tax, Section 409A: Fifteen Years Later, KPMG (Dec. 16, 2019), https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/us/pdf/2019/12/tnf-wnit-section-409a-dec16-2019.pdf

Robin Ji, Maximizing Employee Upside: Everything You Need to Know About Navigating 83(b) Elections in Token Compensation, Liquifi (Feb. 1, 2024), https://www.liquifi.finance/post/83b-elections-token-vesting-grants

Robin Ji, Token Vesting and Allocations Industry Benchmarks, Liquifi (June 15, 2022), https://www.liquifi.finance/post/token-vesting-and-allocation-benchmarks

Robin Ji, When To Use Vesting vs Lockups For Your Tokens, Liquifi (Nov. 23, 2022), https://www.liquifi.finance/post/when-to-use-vesting-vs-lockups-for-your

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table 5. Number of private sector establishments by age (1991-2004), https://www.bls.gov/bdm/us_age_naics_00_table7.txt-token

What Is a Governance Token?, Ledger (Mar. 22, 2022), https://www.ledger.com/academy/what-is-a-governance-token-and-why-does-it-matter

What Is a Token Generation Event (TGE)?, BitDegree (Jul. 07, 2023) https://www.bitdegree.org/crypto/learn/crypto-terms/what-is-token-generation-event-tge

Jessica Furr, Read the Fine Print for Stock Options, The LawVerse (May 09, 2025), https://www.thelawverse.com/p/fine-print-for-stock-options

Disclaimer: This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This post reflects the current opinions of the author(s) and are for educational purposes only. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without notice.

Images: All original images are AI-generated with using a combination of Dall-E, Firefly, DreamStudio and Pixlr.

There are obvious exceptions, including, for example, tokenized stock, which is literally just shares that have been digitized and can be transferred on a blockchain rather than through a brokerage.

Governance tokens allow holders to vote on protocol upgrades or treasury use, but they don’t have enforceable ownership or profit-sharing claims under corporate law the way stock does. They also do not result in unilateral control: tokenholders can only influence the parameters that were hard-coded into the project’s governance framework at inception. Voting stock, on the other hand, is a legal equity interest: it carries statutory rights, fiduciary protections, and economic entitlements.

Some law firms will create token documentation before a token is minted, but those may be structured as future token interests. Other firms may take the position that you can't file an 83(b) until you have dominion and control over the token itself.

Note: taxpayer may still have tax ownership of the property even if subject to certain restrictions, which may impact timing of taxability upon receipt and holding period.