LawBurst: Could CrowdStrike Dodge a 'Birdstrike' of Lawsuits

How the Tech Veil Could Help CrowdStrike Escape Liability for Its Faulty Software

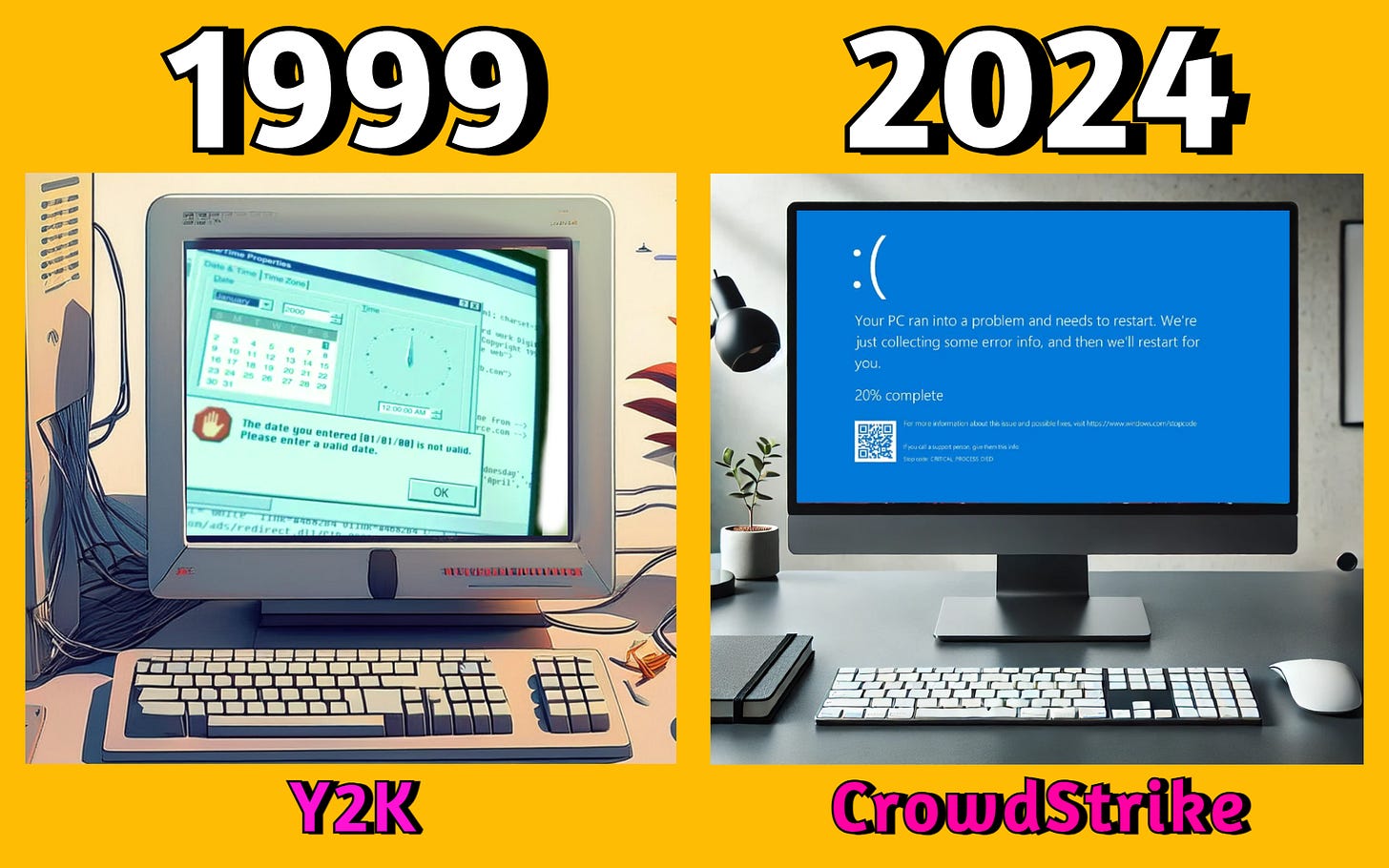

On December 31, 1999, adorned in chokers and elevated by platform shoes, we were torn between playing Snake on our Nokias or Pokémon on our Gameboys, all while counting down the American Top 40 with Casey Kasem (RIP Shaggy) to that number-one hit, Smooth by Santana featuring Rob Thomas. Together, we collectively held our breath, awaiting the stroke of midnight and the dawn of a new millennium.

Y2K was supposed to bring chaos: computers crashing, planes falling, power outages, nuclear war, and the end of civilization as we knew it. But after the clock hit midnight on January 1, 2000, nothing much happened.

25 years later, we got the Y2K no one knew was coming in the major IT outage during the summer of 2024 that affected almost 8.5 million devices. The cause? A defect in a software update sent out by cybersecurity vendor CrowdStrike.

In this follow-up to the previous article, The Untouchables: Why Software Companies Escape Liability for Faulty Software?, we’ll lay out how CrowdStrike could leverage the legal protections to shield itself from liability from the various lawsuits related to the massive IT hiccup.

I. CrowdStrike and the IT Outage

CrowdStrike’s core technology is Falcon, a platform designed to prevent cybersecurity breaches. On July 19th, 2024, CrowdStrike pushed out a routine software update for Falcon—or so it thought. Operating off of a successful stress check done in March 2024, it seems CrowdStrike assumed the best and skipped some tests before pushing the July update, allowing a flaw to sneak through. With no phased rollout, the flawed update went out to everyone once released. Since Falcon is tightly integrated with Microsoft Windows, when the flaw crashed Falcon, down went the millions of Windows systems connected to it.

The outage affected airlines, hospitals, banks, media outlets, hotels, retail stores, stock markets, emergency services. Particularly affected was Delta Airlines, which relied on Windows for over half of their IT systems and accounted for nearly ⅔ of all canceled flights worldwide. And while CrowdStrike was able to find and push out a fix to the update file in 79 minutes, the disruption in many places went on longer. Many systems were stuck on the “Blue Screen of Death,” requiring manual reboots to get them out of the crash loops they were stuck in. The outage caused worldwide financial damage of at least $10 billion, with insurers estimating that U.S. Fortune 500 companies took $5.4 billion in losses.

II. A Deluge of Lawsuits

Every party affected by the outage—CrowdStrike shareholders, Delta passengers, Microsoft, Delta, and CrowdStrike themselves—all seem to have an opinion as to who and how people should be held responsible. Here are some of the outstanding lawsuits CrowdStrike is facing related to this incident that we’ll discuss:

CrowdStrike Sued by Air Passengers: CrowdStrike was sued in a class action by air travelers whose flights were delayed or canceled. They say CrowdStrike was negligent in testing and deploying its software and want compensation for their disrupted flights, as well as punitive damages.

Note that Delta was sued by passengers in a separate class action for breach of contract over how it handled refunds, with passengers also seeking compensation for travel disruptions.

CrowdStrike Sued by Delta (and counter sues!): Delta sued CrowdStrike on October 25th citing $500 million in losses. Delta has accused CrowdStrike of gross negligence, misrepresentation, computer trespassing, trespass to personal property, strict liability, breach of contract, and deceptive and unfair business practices. Delta is seeking monetary and punitive damages.

CrowdStrike countersued to seek declaratory judgment that it wasn’t responsible for Delta’s claimed harm, noting Delta repeatedly declined help from CrowdStrike and Microsoft.

[CrowdStrike was also sued in a class action by its own shareholders as the shareholders say that CrowdStrike made false and misleading statements about their software testing. The shareholders want compensation after share prices dropped 32% post-outage, and $25 billion in market value was wiped out. For brevity, we’ll not discuss this suit.]

III. Can CrowdStrike Escape? The “Tech Veil” in Action!

Despite Delta’s chest puffing, holding software companies liable for tech defects isn’t easy. This is partly because products (and software lawsuits) are complex, partly because companies create defenses in contracts, and partly because of industry norms. Each of these issues can function as a “moat”: a competitive advantage for software companies and a deterrent for everyone else. We’ll walk through the implications of each moat within the Tech Veil that protects software companies from liability.

A. Recap of the “Tech Veil”

Litigation Moat: Software companies can face litigation for breach of warranty, negligence, or strict liability, but each claim has significant challenges. Breach of warranty requires a contract, which often limits damages, and limited damages often make lawsuits unattractive. Negligence claims are hard to win due to difficulties proving direct harm, especially with third-party involvement. Strict liability is rare since it only applies to software causing significant physical or property damage.

Contractual Moat: Software companies build defenses into their contracts by disclaiming warranties, limiting liability, and including indemnity clauses. Disclaiming warranties reduces the company's promises, limiting grounds for lawsuits. Liability limitations cap or restrict damages, and indemnity clauses can shift legal defense costs to the consumer if the company is sued due to the consumer's use of the software.

Structural Moat: Certain legal barriers and norms help shield tech companies. For one, the software industry itself argues that flaws are inevitable. Software is complicated and the components are intricate. Serious errors can slip by, with some of those issues only being discovered through real-world reviews and tests. But the fix, software companies argue, is not to hold them to a higher, more sensitive standard of liability. Software companies say that would slow development, inhibiting innovation and resulting in higher prices for consumers. Courts agree, resulting in cases frequently getting tossed out of court or settled for small amounts.

B. How CrowdStrike Could Beat Each Lawsuit

1. Airline Passengers v. CrowdStrike: Negligence

The air travelers bringing a suit against CrowdStrike are alleging negligence, or that the software was carelessly made. In negligence cases, a direct contract isn’t required, but plaintiffs must prove four key elements:

There was a legal duty

The duty was breached

The breach of that duty caused harm

The harm led to damages

Proving negligence in software cases can be tricky because of the duty software companies owe. Unlike other technical professionals (like doctors and lawyers) who are held to a high standard of behavior, software companies are only required to act "reasonably" — i.e. not held to higher standards like doctors or lawyers. This makes it harder to prove they breached their duty, as the average person wouldn't catch every software defect.

Causation is also tricky—plaintiffs must prove the software itself caused the harm, not a third party like Delta, which managed the flights. CrowdStrike has pointed out that Delta was slow to recover, declined offered help, and failed to keep systems updated, shifting blame toward Delta.

Lastly, plaintiffs need to show tangible injury or property damage, which is rare in software-related cases. Punitive damages are even tougher, requiring proof of serious misconduct. Given the complexity of software, companies often argue that issues were unavoidable or due to carelessness, rather than intentional harm or recklessness.

Given these challenges, it seems unlikely that the airline passengers will have an easy win in court. Judges in tort cases like this one are typically cautious about holding a defendant liable for harm that may be too indirect or unforeseeable. With attention also focused on Delta's handling of the situation, there’s much to explore in the chain of causation between CrowdStrike's software error and the flight delays. If CrowdStrike couldn’t have reasonably foreseen Delta's heavy reliance on them or its outdated systems, Delta’s actions may overshadow any negligence by CrowdStrike, potentially shielding the company from liability.

2. Delta v. CrowdStrike: Limitation of Liability

A. Risk Shifting Provisions: Limitation of Liability

CrowdStrike and Delta have also been publicly disputing the extent of CrowdStrike’s liability. In contracts, companies often limit their liability by restricting the types of damages covered, such as excluding indirect or punitive damages, and setting a monetary cap. In a letter to Delta prior to the lawsuit, CrowdStrike wrote that its liability was capped at an amount in the “single-digit millions.” According to CrowdStrike’s complaint, its liability for Delta’s services is capped at twice the fees Delta paid, excludes indirect or consequential damages, and requires Delta to comply with applicable laws (details below).

Delta argues in its complaint, however, that gross negligence or willful misconduct would override the liability cap—something CrowdStrike concedes, if proven (see below). To succeed, Delta must demonstrate that CrowdStrike’s actions were more than just careless. Gross negligence implies a severe lack of care with reckless disregard, while willful misconduct involves intentional disregard for known risks. Both are challenging standards to meet.

Delta points to CrowdStrike’s lack of a staged rollout and its admission that certain tests were skipped as examples of this misconduct. However, software development is complex, and skipping tests or not implementing a staged rollout does not necessarily prove intentional harm.

CrowdStrike points to Delta’s own IT decisions and response failures as primary causes of the slow recovery. It asserts that other companies resolved similar issues more quickly, suggesting Delta’s infrastructure and choices contributed to the impact. CrowdStrike also questions Delta’s compliance with federal cybersecurity requirements, particularly a 2023 TSA mandate for airlines. If CrowdStrike can demonstrate that Delta’s actions contributed to the incident, it could weaken Delta’s claim of gross negligence and reduce CrowdStrike’s potential liability.

What’s very telling is that Delta’s complaint doesn’t mention the limitation of liability language at all, suggesting it knows the only way it can win is to focus on a gross negligence or willful misconduct argument. To do so, it will try to argue that CrowdStrike’s actions were serious enough to warrant unlimited damages. However, CrowdStrike’s lawsuit for a court ruling on liability limits could force Delta to address these caps directly at an early stage of the trial process, potentially limiting Delta’s recovery if the court sides with CrowdStrike.

While these types of cases usually settle, if we get to the discovery phase, it would be interesting to read the full terms, i.e. the reps, warranties and indemnification provisions.

FWIW, CrowdStrike’s online terms and conditions protects it well in these areas:

The warranty limits remedies to problem resolution, workarounds, or a prorated refund, placing maintenance responsibility on the customer, while indemnification is restricted to covering a customer’s defense costs in third-party intellectual property claims only. That’s some protective language!

IV. Final Thoughts: Is Software Getting Worse?

On August 12th, CrowdStrike's President accepted the Pwnie Award for the “Most Epic Fail” in cybersecurity. Just days later, on September 24th, Adam Meyers, CrowdStrike’s Senior VP for Counter Adversary Operations, testified before the House Homeland Security Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection Committee, admitting that CrowdStrike had "let our customers down." This incident is a reminder that software companies must prioritize actual quality assurance over assumptions. CrowdStrike has pledged to implement more software checks and stagger future updates to prevent similar issues.

The global IT outage caused by a faulty CrowdStrike update also illustrates how over-reliance on a few dominant players in sectors like transportation, healthcare, and finance can magnify risks to the public. While the CrowdStrike outage was directly caused by its faulty Falcon update, it was worsened by Microsoft's dominance in enterprise software. Windows systems, which are used globally in corporate and public infrastructure, were disproportionately affected. Though Microsoft wasn’t directly responsible, the widespread reliance on its systems amplified the consequences. Critics argue this is a prime example of the dangers of technological “monocultures,” where too many organizations depend on a single platform, increasing the impact of any failure. Tech folks have suggested this reflects the need to diversify software solutions across industries to reduce the risk of widespread outages.

Addressing these issues would require significant changes in industry priorities. Currently, the focus is on fast software development to serve more consumers and stay competitive in a market dominated by a few major players. Speed, in this case, isn’t a bug—it’s a feature. However, speed without reliability benefits no one. Without regulations addressing software monopolies and effective private regulation via lawsuits, companies are free to make repeated mistakes, leaving consumers with limited alternatives.

We've seen how courts hesitate to impose broad liability on tech companies, and how software firms promote the narrative that change is difficult, if not impossible. It may take an act of Congress to truly shift the status quo and penetrate the “Tech Veil.”

For now, death, taxes, and software bugs remain the only certainties in life.

[Special thanks to Sam Silverberg.]

Resources:

https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/Explaining-the-largest-IT-outage-in-history-and-whats-next

https://www.theverge.com/2024/7/24/24205020/crowdstrike-test-software-bug-windows-bsod-issue

https://assets.law360news.com/1868000/1868027/crowdstrike%20response%20letter%20(2024.08.08).pdf

https://assets.law360news.com/1868000/1868027/crowdstrike%20response%20letter%20(2024.08.08).pdf

https://www.pcmag.com/news/crowdstrike-exec-shows-up-to-accept-most-epic-fail-award-in-person

https://www.reuters.com/technology/crowdstrike-exec-testify-before-congress-it-outage-2024-08-30/

https://moduscreate.com/blog/unrealistic-expectations-dangerous-piece-software/

https://stackoverflow.blog/2023/12/25/is-software-getting-worse/

https://www.wsj.com/business/airlines/delta-sues-crowdstrike-over-july-operations-meltdown-099ad8fa

https://www.reuters.com/legal/crowdstrike-delta-sue-each-other-over-flight-disruptions-2024-10-28/

Delta Air Lines, Inc. v. CrowdStrike, Inc. - complaint filed on 10/25/24

CrowdStrike, Inc. v. Delta Air Lines, Inc. - complaint filed on 10/25/24

AI Images:

Image of Y2K generated by Dall-E, Firefly, DreamStudio and Pixlr

Image of Blue Screens of Death generated by Dall-E, Firefly, and Pixlr

Image of 3 Moats generated by Dall-E, Firefly, and Pixlr

Image of Whack-A-Mole generated by Dall-E, Firefly, and Pixlr

Image of Bird Strike generated by Dall-E, Firefly, and Pixlr

Image of Falcon in Tech Veil generated by Dall-E, Firefly, and Pixlr

Image of Ben Franklin generated by Dall-E, Firefly, and Pixlr

Disclaimer: This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. This post reflects the current opinions of the author(s). The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.