How Could SVB File For Bankruptcy And Be Under Receivership? Implications for Crypto

Understanding the difference between receivership and bankruptcy regimes and how it applies to crypto assets

In the words of the poet Robert Frost, “Nothing gold can stay.” The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) left many of us in the tech world shell shocked. SVB was a key player in the startup ecosystem for decades so it’s sad to see the end of an era. With the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) agreeing to backstop all deposits and later brokering a deal to sell SVB to First Citizens, we can all take a collective breath, switch off our panic buttons, and find a teachable moment.

The news coverage during the weeks that SVB collapsed did not explain very clearly how SVB could both be under receivership with the FDIC and file for bankruptcy at the same time. How exactly does that work? Without further ado, let’s double click to understand what it means to file for bankruptcy vs. being put into receivership, the impact of each path, and why it matters, particularly for consumers and crypto.

Difference between Bankruptcy and Receivership

Bankruptcy

Most companies that need to go through an insolvency process file for bankruptcy under the US federal bankruptcy code. Filing for bankruptcy allows a company to seek relief for debt obligations it’s unable to honor by coming up with a plan to (i) repay debt and (ii) either stay in business or dissolve completely. To clarify some definitions, a debtor is the party that files for bankruptcy, and a creditor is the party to whom a debtor owes money.

Failing companies (debtors) can choose to file for bankruptcy themselves or they can be forced into bankruptcy by their creditors. Bankruptcy cases are governed by federal law and thus processed through federal courts where a judge ultimately determines whether a debtor may file for bankruptcy and, if so, whether the debts can be forgiven. Often times, the case will be handled by a bankruptcy trustee who is appointed by the Department of Justice’s US Trustee Program. Trustees are in charge of collecting as much money from the bankrupt company’s estate (all the property of the debtor, which includes what it owns and what it controls) and dispersing it to creditors. Sometimes, instead of a trustee, a Chapter 11 debtor will keep the business running itself on behalf of creditors (called a debtor in possession (“DIP”)), and a group of creditors (called a creditors committee) will monitor the activities of the DIP. This is what’s happening with the FTX bankruptcy.

Receivership

Per the US bankruptcy code (11 U.S.C. § 109(b) and (d)), certain persons may not file for bankruptcy under Chapter 7 (liquidation) or Chapter 11 (reorganization), including: “domestic insurance company, bank, savings bank, cooperative bank, savings and loan association…credit union, or industrial bank or similar institution which is an insured bank.” For those listed exceptions, there are other statutory regimes that would apply to each of them; specifically, in the case of banks, they are subject to the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (“FDIA”).

Per the FDIA, an insured bank that collapses is put under receivership by the FDIC, which in turn, tries to locate a buyer to assume the failed bank’s assets and liabilities. If the FDIC is unable to find a buyer, it will sell all of the failed bank’s assets and distribute the proceeds to the creditors based on the priority of the claims. In general, up to $250,000 per depositor per FDIC-insured bank per ownership category is insured (though there are exceptions to this general rule) – or to put it simply, if you have money in a bank that goes under, you can get up to $250,000 back. The FDIC is required to find the most efficient, cost-sensitive resolution, and it has expansive statutory authority to ensure and expedite the receivership process.

A Centralized v. Decentralized Process

Bankruptcy is like any other court proceeding in which all the players involved (the judge, debtor, creditor, and trustee) function independently and represent their own interests. It’s a decentralized process in which the judge applies the laws passed by Congress, and the creditors, debtors, and trustee advocate their respective views and positions before the court. It involves lots of discussion and debate between the parties to come to a resolution.

On the other hand, the receivership approach is quite different and centralizes some of those comparable roles and responsibilities you see in a bankruptcy proceeding into one party, the FDIC, which functions as a judge, trustee, debtor, and legislator. The FDIC has congressional powers to step in as a receiver for a failed bank, to administer the bank’s assets without judicial scrutiny, and to make the rules without any (or rarely any) judicial supervision. Hence, receivership is not a collaborative process as the intent is for the FDIC to move quickly to resolve a banking crisis.

Priority of Claims

Under both bankruptcy and receivership processes, there is an order in which obligations, or claims, are paid back to creditors.

For a bank under receivership, the priority of claims goes like this: (i) FDIC administrative expenses (this may be for loans that the FDIC has to make to keep an institution running or afloat), (ii) insured deposits (meaning those backed by FDIC insurance, usually $250,000), (iii) uninsured deposits (those not backed by FDIC insurance), and (iv) general creditors and shareholders (usually, there’s little or no recovery for these claimants).

For a company under bankruptcy, here’s the priority hierarchy: (i) secured creditors (debt backed by collateral), (ii) unsecured creditors (generally debt not backed by an asset but can include tax and payroll obligations, among others), and (iii) equity holders or shareholders.

How Does this Apply to SVB?

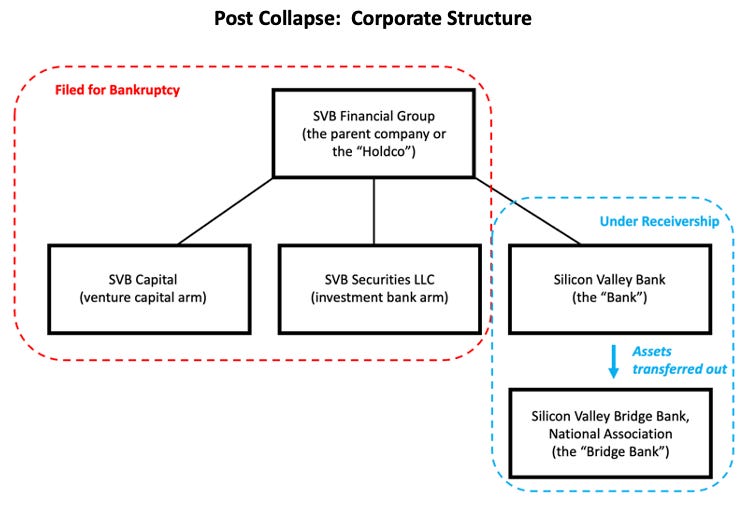

Looking at the corporate entities that made up SVB, at the top of the structure sat the parent company, SVB Financial Group (the “Holdco”), and underneath the Holdco were subsidiaries, including Silicon Valley Bank (the “Bank”), SVB Capital (the venture capital and credit investment arm), and SVB Securities LLC (the investment bank arm).

The California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation shuttered the Bank on March 10, 2023, and because it was an FDIC-insured bank, the FDIC was appointed as receiver. When a bank fails, the FDIC will temporarily create a deposit insurance national bank (in this case called the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara (“DINB”)) to assume the deposits of the failed bank and continue banking services for customers if no other bank is willing to step in. When the Treasury Department decided to cover all the uninsured deposits, the DINB was replaced with a bridge bank called Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, National Association (the “Bridge Bank”). All deposits and substantially all of the remaining assets of the Bank were transferred to the Bridge Bank; such legal engineering is captured in the Transfer Agreement. As a result of this forced restructuring, the Holdco was neither the parent of the Bridge Bank nor affiliated with it.

Forcing the Bank to close and be put into receivership compelled the Holdco to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in New York on March 17, 2023 as it triggered debt defaults and cut off the Holdco from its main revenue generating business line (i.e. the Bank). As subsidiaries of the Holdco, SVB Capital and SVB Securities LLC were also included in the bankruptcy filing. The Bank, being under receivership, was not included in the bankruptcy filing.

Applying the Lessons of SVB for Custodied Assets in Crypto

As evident with SVB, a company going through a receivership vs. a bankruptcy process leads to a different outcome for all stakeholders involved. Let’s examine how this has played out during crypto winter in terms of what happens to consumer assets held in custody with a company that then becomes insolvent.

As background, the types of entities that tend to hold customers’ crypto assets are state chartered trust companies, exchanges, and special purpose depository institutions, which are not banks and upon insolvency, would fall under a bankruptcy regime. For simplicity, I’ll refer to these types of entities as a “Non-Bank Financial Company” (“NBFC”).

Unlike with FDIC-insured banks, customer assets held in a NBFC won’t automatically be segregated from the bankruptcy estate unless the court decides that the relationship between the customer and the NBFC is a custodial relationship (i.e. not a debtor-creditor relationship). Recall, the FDIC has to guarantee up to $250,000 of customer deposits and must separate those deposits from the rest of the bank’s holdings. In a bankruptcy proceeding, the court controls all property and contracts of the debtor, and therefore it may decide to assume, reject or terminate a contract with a customer (or in other words, the court can decide to segregate or not segregate customer assets). If a crypto asset is considered part of the bankruptcy estate, the consumer is considered an unsecured creditor and waits in line to hopefully get some of her money back. However, a customer’s crypto assets held in custody would likely be deemed separate from the bankruptcy estate and returned to the customer.

Bankruptcy courts will scrutinize the agreement between parties to determine whether that agreement created a debtor-creditor relationship or a custodial relationship. Under such fact specific analysis, the court may consider questions such as (i) were customer assets commingled with the debtor’s assets, (ii) could the debtor choose how to use the customer’s property at its own discretion or were there controls in place on how such assets could be used, (iii) was the debtor acting as an agent of the customer by following customer instructions, and (iv) was beneficial title transferred to the debtor? In summary, if the failed institution is not a bank, it falls under bankruptcy purview, which puts it down the road of a judicial determination, which has a less certain outcome.

Celsius

An illustrative example is the bankruptcy proceeding of Celsius Network LLC (“Celsius”). When Celsius filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, one issue that came before the court was whether to treat customer deposits as assets in custody, or belonging to the bankrupt company’s estate. Celsius had offered various products, one of which was the Earn Program, in which a user deposited their digital assets in return for a high interest rate, but it also offered a Custody Program that earned no interest. The judge had to conduct a contractual analysis to determine whether a custodial relationship with customers existed by reviewing Celsius’s customer contracts. According to Celsius’s terms of use dated as of April 14, 2022 (the “Celsius Terms”), the following language relates to the Earn Program:

“In consideration for the Rewards payable to you on the Eligible Digital Assets using the Earn Service . . . and the use of our Services, you grant Celsius . . . all right and title to such Eligible Digital Assets, including ownership rights, and the right, without further notice to you, to hold such Digital Assets in Celsius’ own Virtual Wallet or elsewhere, and to pledge, re-pledge, hypothecate, rehypothecate, sell, lend, or otherwise transfer or use any amount of such Digital Assets, separately or together with other property, with all attendant rights of ownership, and for any period of time, and without retaining in Celsius’ possession and/or control a like amount of Digital Assets or any other monies or assets, and to use or invest such Digital Assets in Celsius’ full discretion. You acknowledge that with respect to Digital Assets used by Celsius pursuant to this paragraph:

1. You will not be able to exercise rights of ownership;

2. Celsius may receive compensation in connection with lending or otherwise using Digital Assets in its business to which you have no claim or entitlement; and

3. In the event that Celsius becomes bankrupt, enters liquidation or is otherwise unable to repay its obligations, any Eligible Digital Assets used in the Earn Service or as collateral under the Borrow Service may not be recoverable, and you may not have any legal remedies or rights in connection with Celsius’ obligations to you other than your rights as a creditor of Celsius under any applicable laws.”

In the court’s view, the language clearly transferred title and ownership from the Earn account holders to Celsius and therefore became the property of the Celsius bankruptcy estate. The Celsius Terms allowed Celsius to have the right to move assets at its discretion and was clear that it had “all right and title to such Eligible Digital Assets.” This meant those Earn Account customers had to wait in line with the other unsecured creditors in the hopes of getting some of their assets back. However, the Celsius judge viewed the Custody Program differently. Per the Celsius Terms regarding the Custody Program:

“Title to any [each customer’s] Eligible Digital Assets in a Custody Wallet shall at all times remain with [the customer] and not transfer to Celsius. Celsius will not transfer, sell, loan or otherwise rehypothecate Eligible Digital Assets held in a Custody Wallet.”

Given (i) the above language intended for customers to retain ownership of their assets in the Custody Program, (ii) such assets weren’t commingled with Celsius funds and (iii) customers weren’t earning interest, the judge held that these digital assets were custodial assets that were not the property of the bankruptcy estate and were therefore to be returned to customers upfront.

FTX

Time will tell what the bankruptcy court does in the FTX case. However, we know that FTX violated their Terms of Use by commingling assets. [For further details on Celsius and FTX cases vis-à-vis bankruptcy, check out LawVerse’s prior article.]

The Lesson for Consumers

It’s important to understand as a consumer (i) what type of entity is holding your assets, (ii) whether your assets are insured and segregated if a company collapses, and (iii) how to mitigate those risks. If using a traditional bank, remember the FDIC normally insures you up to $250,000. If using a NBFC, know you don’t get FDIC insurance, and your asset may not be so easily returned to you.

Resources:

11 U.S.C. § 109(b) and (d) - https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/11/109

12 U.S.C. § 1813 - https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/1813

In re Joliet-Will Cnty. Community Action Agency, 847 F.2d 430, 431 (7th Cir. 1988) (Posner, J), https://casetext.com/case/in-re-joliet-will-cty-community-action-agency-2

In re Celsius Network LLC, et al., Memorandum Opinion and Order Regarding Ownership Of Earn Account Assets, (US Bankruptcy Court, SDNY 2023) (Glenn, M.), https://cases.stretto.com/public/x191/11749/PLEADINGS/1174901042380000000067.pdf

In re Celsius Network LLC, et al., Debtors’ Motion Seeking Entry of an Order (I) Authorizing the Debtors to Reopen Withdrawals for Certain Customers with Respect to Certain Assets Held in the Custody Program and Withhold Accounts and (II) Granting Related Relief, (US Bankruptcy Court, SDNY 2023) (Kirkland & Ellis LLP), https://cases.stretto.com/public/x191/11749/PLEADINGS/1174909012280000000022.pdf

Declaration of William C. Kosturos in Support of the Debtor’s Chapter 11 Petition and First Day Pleadings [Docket No. 21] (Kosturos Declaration): https://restructuring.ra.kroll.com/svbfg/Home-DownloadPDF?id1=MTQ2OTc3Mw==&id2=-1

Allen Matkins - FDIC Resolution and Receivership of Failed Banks: Pitfalls for Landlords - https://www.allenmatkins.com/real-ideas/fdic-resolution-and-receivership-of-failed-banks-pitfalls-for-landlords.html

Fried Frank - An Overview of Debtor in Possession Financing - https://www.friedfrank.com/uploads/siteFiles/Publications/An%20Overview%20of%20Debtor%20Possession%20Financing.pdf

Morrison Foerster - FDIC Bank Receivership Frequently Asked Questions - https://www.mofo.com/resources/insights/230312-fdic-bank-receivership-frequently-asked-questions

Nixon Peabody - What happens in the event of the insolvency of a cryptocurrency business conducted through a “bank”? - https://www.nixonpeabody.com/insights/alerts/2022/06/10/what-happens-in-the-event-of-the-insolvency-of-a-cryptocurrency-business-conducted-through-a-bank

Sidley - Implications of Silicon Valley Bank Closure - https://www.sidley.com/en/insights/newsupdates/2023/03/implications-of-silicon-valley-bank-closure

FDIC - When a Bank Fails - Facts for Depositors, Creditors, and Borrowers, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation - https://www.fdic.gov/consumers/banking/facts/

FDIC Creates a Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara to Protect Insured Depositors of Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California - https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23016.html

FDIC Acts to Protect All Depositors of the former Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California - https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2023/pr23019.html

FDIC Dividends from Failed Banks - https://closedbanks.fdic.gov/dividends/

FDIC – Transfer Agreement - https://www.svb.com/globalassets/bridge-bank/silicon-valley-bdi-transfer-agreement-03.13.23sign.pdf

Axios - Mapping out Silicon Valley Bank's businesses - https://www.axios.com/2023/03/18/silicon-valley-bank-corporate-map

NY Times - Silicon Valley Bank Sold to First Citizens in Government-Backed Deal - https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/27/business/silicon-valley-bank-first-citizens.html

Reuters - Silicon Valley Bank's parent company cut off from bank's records - https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/silicon-valley-banks-parent-company-cut-off-banks-records-2023-03-20/

Image of Federal Bankruptcy Code generated by ChatG

Disclaimer: This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. This post reflects the current opinions of the author(s). The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.