Antitrust Law is Cool Again

How the Neo-Brandeis Movement is Going on the Offensive against Big Tech

Antitrust hasn’t always been an area of the law where the cool kids hung out; its relevance throughout history has ebbed and flowed depending upon the historical circumstances and the cast of characters involved. Today, antitrust is once again “straight fire,” with the nerds taking over the school as years of limited regulation in the tech industry have led to a boiling point over issues like social media misinformation and AI’s existential risks.

The first domino might have already fallen, with the D.C. District Court recently ruling against Google in the biggest US antitrust trial in decades. It could signal a broader trend, with antitrust suits pending against Apple, Google (part 2), Amazon, Visa, and Meta. Interestingly, these lawsuits have supporters from both sides of the aisle (regulating tech might be the last purple issue). While commentators disagree on why Big Tech presents antitrust concerns, they can agree that the concentration of power in tech is a problem. The result is a philosophical shift among antitrust enforcement agencies who are ramping up scrutiny of Big Tech.

Antitrust law, originally designed to curb the abuses of monopolistic titans like Standard Oil, has evolved dramatically over the years, particularly with the rise of the consumer welfare standard in the 1970s. Today, as Big Tech dominates the global market, antitrust enforcement is shifting again, moving beyond consumer prices to focus on the broader impact of corporate power on competition, innovation, and even democracy itself. This article explores how antitrust laws have developed, the challenges of regulating in the digital age, and how current legal battles are shaping the future of tech regulation in the United States.

Roadmap:

I. Antitrust Explained: History Repeating Itself All Over Again… A. Background on Antitrust Laws B. Who Brings Antitrust Lawsuits? C. Origin Story: Standard Oil and the Robber Barons D. The Chicago School, Robert Bork and the Rise of the Consumer Welfare Standard (1970s) E. Microsoft Loses Antitrust Case (2000)…Kinda II. Vintage Antitrust: Pivot From Protecting Consumer Welfare Back To Competition A. The Limits of Consumer Welfare Model on Big Tech B. The New Brandeis Movement and Big Tech III. DOJ V. Google - Round 1 Goes To The Government A. The Ruling B. Would Remedies Realistically Be Effective? IV. The Reformation Of Antitrust Law And Reactions V. How Has Big Tech Dodged Antitrust Violations Until Now A. Antitrust Compliance Programs B. Avoidance Mergers: Special Dividends and Acqui-Hires and Poaching VI. Final Thoughts: The Past And The Future VII. Extra Credit: Cases To Keep On Your Radar VIII. Resources

I. Antitrust Explained: History Repeating Itself All Over Again…

A. Background on Antitrust Laws

Why do we have them? Antitrust laws are all about encouraging innovation and ensuring big companies don’t abuse their power, keeping competition fair. It’s fine for a company to take over a market by offering something better, but problems start when a party uses its position to shut out new, creative competitors. These laws are there to stop shady tactics like paying off suppliers to avoid working with rivals, which hurts competition. Exclusive deals happen in business, but they need a closer look to make sure they’re not too restrictive. The goal is a healthy, competitive market where businesses can come and go easily, and consumers get clear info to make smart choices. By keeping big companies from unfairly blocking competition or misleading customers, antitrust laws keep the marketplace fair for everyone.

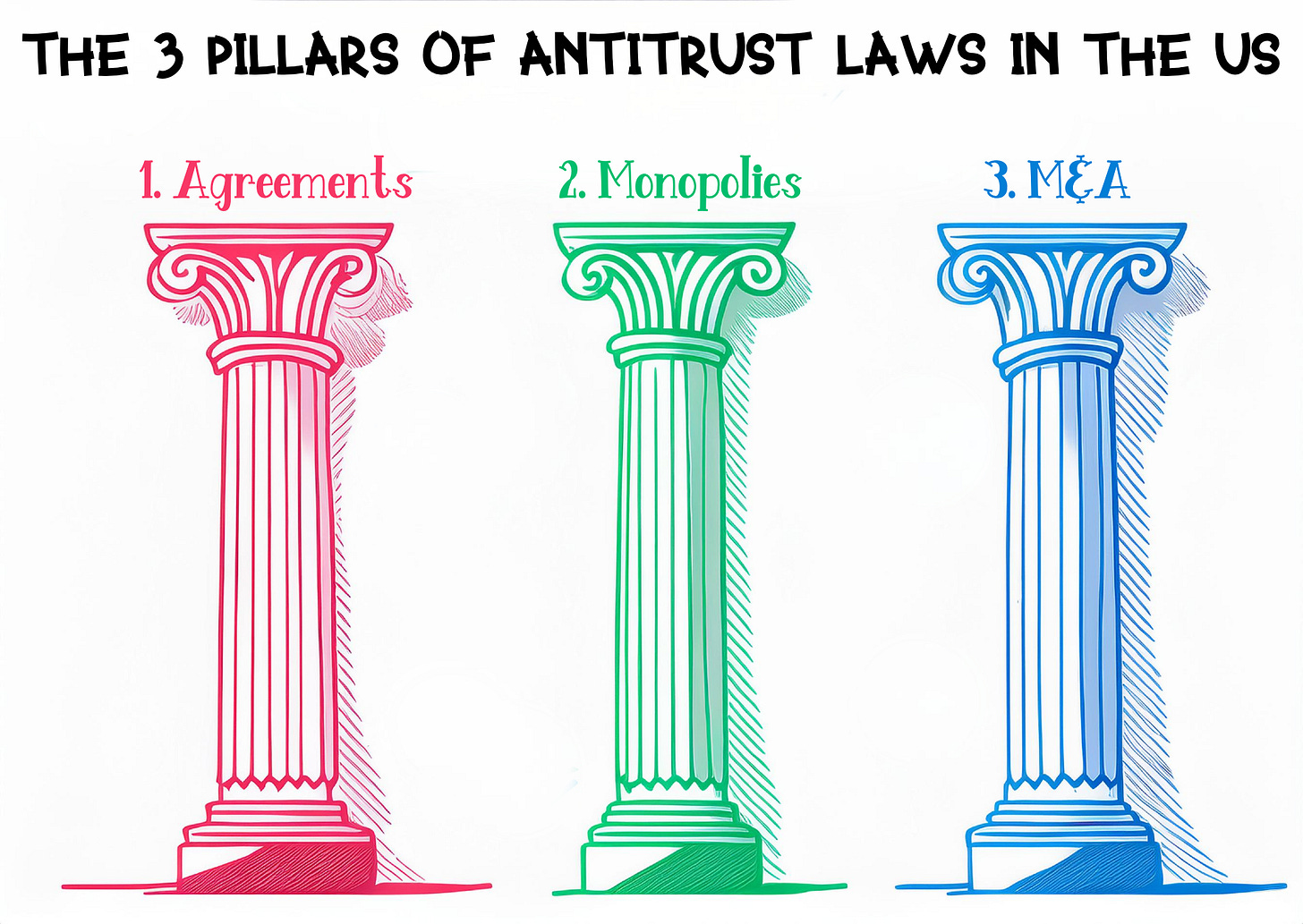

TL;DR on the Law: Three main statutes govern antitrust law in the US: (i) The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, (ii) the Clayton Act of 1914, and (iii) the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. These laws among others are the framework for the three “pillars” of prohibited behavior:

Agreements to Limit Fair Competition (i.e. Two Parties Acting Together): Section 1 of the Sherman Act outlaws agreements between parties to unfairly restrain trade. This could include competitors agreeing to (i) fix prices, (ii) limit output, (iii) submit fake or coordinated bids to win a contract, or (iv) divide up markets and customers, among others. These kinds of agreements are considered automatically illegal (called “per se illegal”). If an agreement is less obviously harmful, courts use a "rule of reason" standard to figure out if it's illegal (i.e. the court has to do some analysis on the overall big picture).

Monopolies (i.e. One Party’s Actions): Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolies that act unfairly to limit competition. A company breaks this law if (i) it controls a large part of the market (called “dominant position”) and (ii) uses its power to block or crush competitors through unfair practices (the legal jargon used here "predatory" or "exclusionary").

Anti-Competitive Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A): Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers and acquisitions (when one company buys another) if they reduce competition or create a monopoly. If a company buys a competitor to limit competition, it can be illegal. Note, the Sherman Act can also be used to stop mergers that result in monopolies or trade restraints.

B. Who Brings Antitrust Lawsuits?

Two federal agencies enforce the antitrust laws: the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”). One might think we have two antitrust enforcement agencies because we value competition, but this redundancy is partly due to (i) historical developments (the DOJ was the enforcer under the Sherman Act while the FTC was established under the Federal Trade Commission Act) and (ii) a desire for specialized expertise.

The DOJ’s antitrust division, headed by Jonathon Kanter, is the historic and general enforcer of antitrust laws. It handles all criminal enforcement while also doing complex civil enforcement. DOJ also has specific statutory authority in areas like banking, telecommunications, airlines, and railroads.

The FTC, chaired by Lina Khan, is the expert in antitrust. It focuses on civil action (potentially through their own administrative court) particularly in consumer protection, advertising, and unfair competition, often targeting sectors like healthcare, pharmaceuticals, professional services, food, energy, and high-tech industries like computing and internet services.

Prior to investigating anyone, the agencies will coordinate so they don’t both bring a lawsuit against the same offender. Although antitrust is known for being more of a federal thing, states have their own antitrust statutes, and the offices of the attorney general in each state are in charge of enforcing them. More on that here.

But how did we get here in the first place? Why do we have these laws?

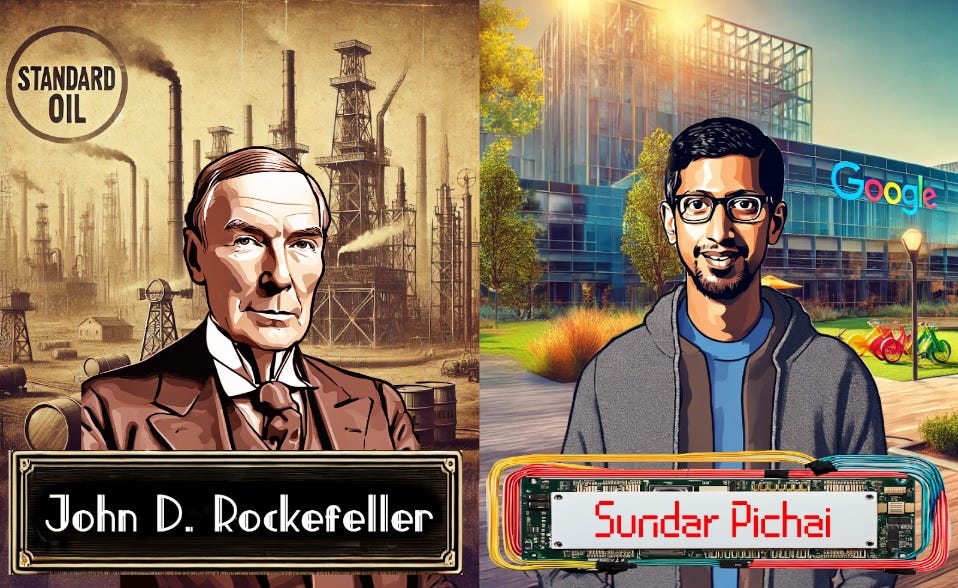

C. Origin Story: Standard Oil and the Robber Barons

To understand the birth of antitrust laws, we have to go back to the late 19th Century – a period known as the Gilded Age. An epoch marked by massive income inequality, political corruption, industrialization, and the rise of powerful monopolies. This was a time when the captains of industry, known as robber barons, like Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan would, according to rumors of the time, go to Delmonico’s, one of NYC’s most exclusive restaurants at that time, roll up hundred-dollar bills and smoke them – just because they could.

This concentration of wealth was evident among both corporations and individuals. Among the smoke-filled drawing rooms of the Jekyll Island Club was America’s first billionaire John D. Rockefeller, who founded Standard Oil in 1870, a company that along with Andrew Carnegie’s US Steel, inspired lawmakers to pass the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. Standard Oil was notorious for its aggressive business strategies like undercutting competitors, restricting supply chains, and procuring exclusive contracts with railroads. At its peak, Standard Oil controlled 90% of US oil production (hmm….sounds like Google).

In 1911, the Supreme Court struck down Standard Oil’s practices, ruling that it violated Sections 1 and 3 of the Sherman Act (pillar 1 and 3) and ordering its breakup into smaller companies. While Standard Oil may seem like a no-brainer example of antitrust violations, in reality, determining whether a violation had occurred was surprisingly tricky for the government. Standard Oil consolidated many of its entities into a single trust, purposefully designed to obfuscate any governmental scrutiny. As muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell (who exposed Standard Oil’s dealings) wrote, “You could argue its existence from its effects, but you could not prove it.”

Going into the early 20th Century, antitrust enforcement was strong, focused on breaking up monopolies like Standard Oil and Northern Securities under Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft. This "trust-busting" period aimed to limit corporate power and promote fair competition. Key laws, including the Clayton Act and Federal Trade Commission Act, were introduced to strengthen the Sherman Act, preventing large corporations from using unfair practices to dominate industries.

Then, a new philosophy changed everything.

D. The Chicago School, Robert Bork and the Rise of the Consumer Welfare Standard (1970s)

In the 1970s, the Chicago School of Economics, led by figures like Robert Bork, prompted a rethinking of antitrust law’s goals. They argued that large firms could achieve efficiencies that benefit consumers, and that market concentration wasn’t necessarily harmful unless it resulted in higher prices or reduced consumer choice.

The consumer welfare model gained momentum as it aligned with the broader pro-market, deregulation trends of the 1970s and 1980s, influencing courts and policymakers. This shift reduced the scrutiny of mergers and market concentration, with fewer cases brought against dominant firms unless there was clear evidence of consumer harm, primarily through price increases.

This trend continued into the 1980s through the Reagan era and beyond, persisting until the 1990s, when regulators began scrutinizing the rise and market dominance of major tech companies.

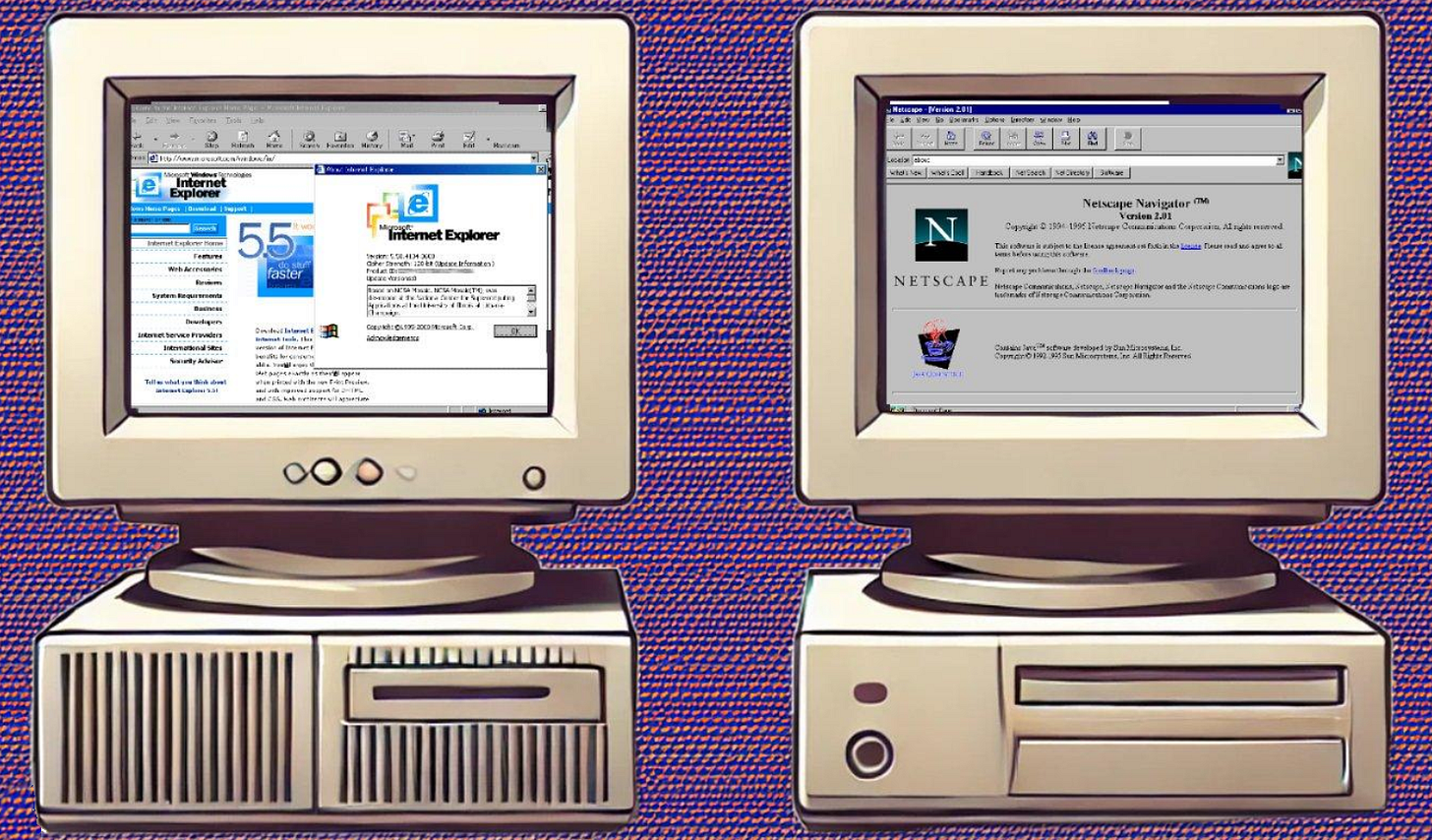

E. Microsoft Loses Antitrust Case (2000)…Kinda

The first company in the crosshairs of the government in this new era was Microsoft. At the time, Microsoft controlled 90% of the PC operating system market. A federal judge ruled that Microsoft had abused this monopoly by bundling its Internet Explorer browser with Windows, effectively stifling competition from browsers like Netscape, which once held over 80% of the market. By giving Internet Explorer away for free and bundling it with Windows, Microsoft eroded Netscape’s market share and blocked innovation, actions that were ultimately deemed anticompetitive. The case not only highlighted Microsoft's effort to eliminate potential middleware competitors like Netscape, which could have diminished Windows' dominance, but also set important precedents for how tech giants wield power—especially when offering "free" services to consumers.

(Sounds like Google).

Surprisingly, despite the judge initially ordering Microsoft to be broken up, the company settled with the DOJ on appeal in 2001. Instead, the settlement-imposed restrictions on Microsoft’s business practices, including requirements to share its application programming interfaces (APIs) with third-party developers and limitations to ensure fair competition.

Why did the DOJ settle with Microsoft? Well, in 2001, the Clinton administration was out, and the Bush administration was in. Although courts had found Microsoft guilty of using its power to unfairly dominate competitors, breaking up the company was seen as too extreme, and constant monitoring wasn’t practical. Instead, the settlement required Microsoft to share more of its software with competitors, allowing them to develop products compatible with Windows. This compromise aimed to move the tech industry forward, but critics argued it didn’t do enough to rein in Microsoft's control, leaving room for future monopolistic behavior.

While the settlement wasn’t as severe as it could have been and allowed Microsoft to retain its dominance in the operating system market, it also made the company more cautious. Increased regulatory scrutiny slowed its expansion into new markets like mobile and internet services. This shift in focus created opportunities for new players to capitalize on this changing landscape.

Ironically, the antitrust case against Microsoft cleared the path for Google to rise as a new tech giant. Now, Google is finding itself in the crosshairs of its own antitrust battles.

History has a way of repeating itself.

II. Vintage Antitrust: Pivot From Protecting Consumer Welfare Back To Competition

A. The Limits of Consumer Welfare Model on Big Tech

As the digital age progressed, the Chicago School's focus on consumer welfare in antitrust law—primarily concerned with price—faced increasing criticism. Under this theory, as long as a company’s actions led to lower prices, courts rarely intervened, even when the company held significant market share. While effective for traditional industries, this approach proved inadequate for tech giants like Amazon, Google, and Facebook, which could dominate markets without raising prices, offering low-cost or free services instead.

These companies operate in complex, multi-sided markets, often acting as both platforms for sellers and competitors. They also benefit from network effects, where their services become more valuable as more people use them, making it difficult for smaller competitors to thrive. This shifted the focus from price to non-price harms like reduced innovation, exclusion of competitors, and control over data, revealing the limitations of the consumer welfare model in addressing modern monopolistic practices.

B. The New Brandeis Movement and Big Tech

Today’s antitrust enforcers (like Lina Khan, Chair of the FTC, and Jonathan Kanter, head of the DOJ’s Antitrust Division) embrace Neo-Brandeisianism (aka the New Brandeis Movement or the Neo Brandeis Movement). Named after Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, this approach emphasizes a broader view of competition, focusing less on consumer prices and more on how large corporations harm competition (particularly for small businesses) and stifle innovation. Brandeis was a key figure in early 20th-Century antitrust philosophy and focused more on competition and less so on price. Critics have called Neo-Brandeisianim “hipster antitrust,” arguing that it tries to use antitrust law to address social issues like inequality, which they believe it wasn’t designed to handle. They worry it could lead to overregulation and political interference in business

Judges in cases brought by the DOJ under Kanter and the FTC under Khan also seem skeptical of Neo-Brandeisianism, and both agencies have suffered a string of losses in court. In the FTC's cases against the Microsoft-Activision and Meta-Within mergers, and the DOJ's case against UnitedHealth Group-Change Healthcare merger, the courts found insufficient evidence that these mergers would significantly harm consumers. The judges felt these cases were based on novel antitrust theories that lacked enough concrete evidence. Courts often focus on immediate, demonstrable harm to competition or consumers, so without clear proof of negative impacts—such as higher prices—they are less likely to block mergers, even when broader, more speculative antitrust theories are presented.

Amid facing skepticism from courts and critics, Khan and Kanter have continued to pursue high-profile litigation against Big Tech. Their strategy isn’t just about winning individual cases—it’s also about educating the public and pushing Congress to update antitrust laws for the digital age.

III. DOJ V. Google - Round 1 Goes To The Government

A. The Ruling

Despite suffering such loses, Kanter and Khan’s efforts are paying off in a big way (to the power of googol). In August 2024, the D.C. District Court dealt a major antitrust blow to Big Tech, with Judge Mehta ruling that Google had illegally maintained its monopoly over (i) internet search and (ii) search text ads—a significant victory (pillar 2) in the ongoing efforts to rein in tech giants.

Search

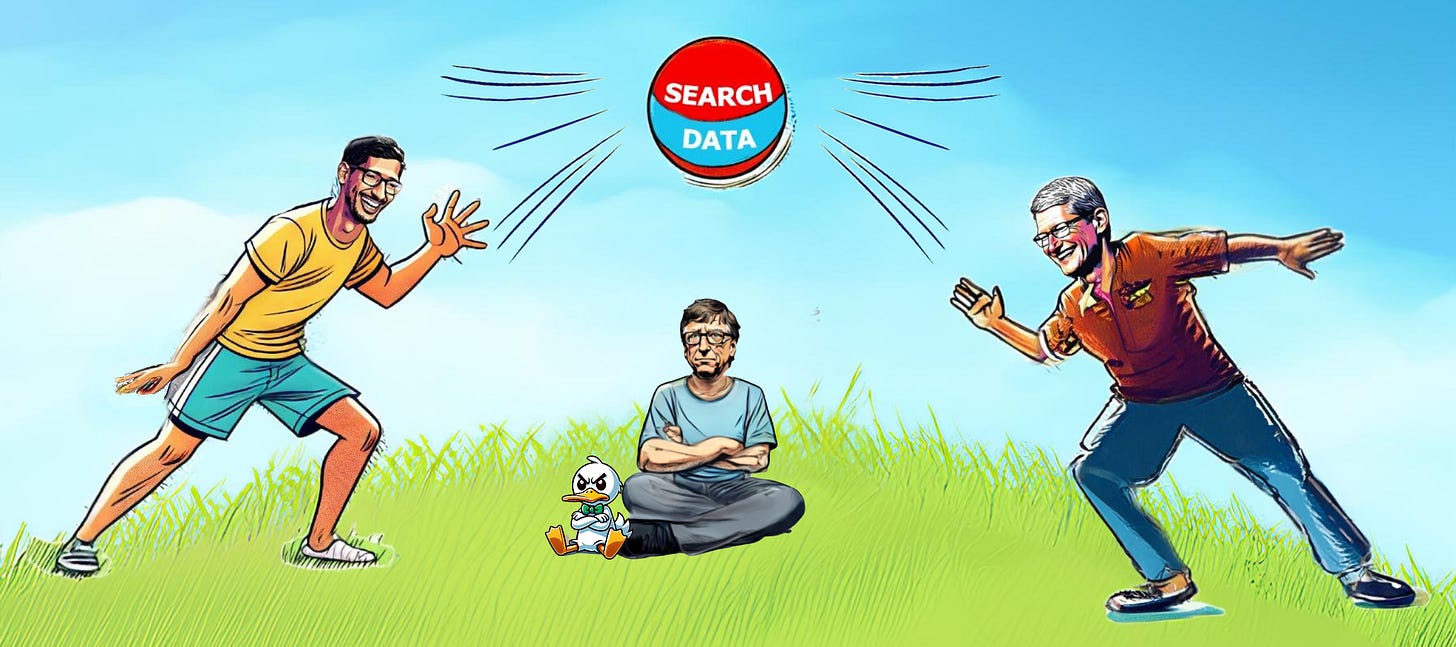

Google engaged in behavior that harms competition by making exclusive contracts, primarily with device manufacturers and carriers, to make its search engine the default engine on smartphones and web browsers and block its competitors.

Google has argued that it dominates the market because its product is the best, so it was simply benefiting consumers by providing them with the best product. Well, let’s think about that assertion. Google paid Apple $20 billion a year to be the default search engine on Apple devices and around 50% of all search queries come from such default placements. The Apple agreement also prohibits Apple from making its search features better than Google’s. Siri and Spotlight, for instance, cannot be meaningfully improved without risking a renegotiation of the deal. Perhaps the most surprising condition of the deal is Apple's obligation to defend Google in the face of regulatory scrutiny!

As a result of deals like this, Google controls around 90% of the online search market (wow, there’s that number again) and 95% of search on smart phones. That market share also gives Google a leg-up in collecting uber valuable user data. For example, Google is able to gather as much user data in 13 months as Bing can accumulate in 17 years. All of this creates a flywheel effect and being so entrenched makes it hard to dethrone it. So is Google really on top because of its superior product, like it argued? Or does it rule because of it entrenches itself through superior negotiating power?

Search Text Ads

Regarding the search text ads (not to be confused with the general search ads), Google acted anti-competitively by gradually raising ad prices in a way that masks the increases through auctions, making it seem like price fluctuations are due to demand when in reality, Google was just inflating prices. This behavior showed Google could raise prices without concern for competitors, which is a clear sign of monopoly power. Judge Mehta called out this pricing manipulation as both monopolistic and unethical.

Ultimately, the fact that Judge Mehta rejected Google’s consumer benefit argument, one grounded in traditional antitrust theories, is a victory for Khan’s Neo-Brandeism. Despite the fact that Google’s dominance is arguably super convenient for consumers, it was not a get-out-of-jail-free-card for Google; this falls perfectly in line with the type of antitrust jurisprudence that Kanter, Khan and the Neo Brandeisians would be in favor of.

B. Would Remedies Realistically Be Effective?

On Tuesday, October 8th, the DOJ announced that it might seek to break up Google as a potential remedy (penalty). Per its court filing, “Fully remedying these harms requires not only ending Google’s control of distribution today, but also ensuring Google cannot control the distribution of tomorrow.” Judge Mehta is expected to decide on a remedy to this situation by summer 2025; meanwhile, Google will appeal the case.

The DOJ’s requested breakup seems improbable. A breakup of Google’s complex business structure would be difficult, and breakups are an extreme remedy anyway. While Judge Mehta has avoided signaling specific remedies, the focus is likely to be on prohibiting Google’s exclusive contracts, possibly through a “choice screen” where users can select their preferred search engine, which is what was done in the EU’s antitrust cases against Google. It’s also doubtful whether consumers, given the choice, would choose to switch away from their old friend Google. But AI could change all that too.

Critics of the antitrust action argue that forcing Google to change its agreements with device manufacturers and carriers could undermine innovation and leave consumers worse off by weakening products many rely on for their quality. It could for example lay a death blow to Mozilla’s Firefox web browser, which relies on an exclusivity agreement with Google for over 80% of its operating budget. Even if apps like Firefox survive, Google’s litigation costs—and any costs it passes onto consumers—could outweigh any benefits consumers see. Ultimately, while remedies aim to boost competition, their full impact will unfold slowly over years, with potential appeals further delaying the process.

Nevertheless, Judge Mehta’s ruling in the Google antitrust case is significant as it may guide future Big Tech cases, particularly on market definition, default settings, and scale. It acts as a "test case" that could influence future rulings and might prompt companies like Alphabet or Amazon to restructure, potentially spinning off YouTube or AWS, to avoid harsher penalties.

IV. The Reformation Of Antitrust Law And Reactions

Clearly, the Neo-Brandeisists think antitrust needs to be reformed to be practical to the realities on the ground, but how could they be reformed practically?

One type of proposed reform would make merger rules stricter and clearer to prevent Big Tech companies from consolidating power even more. For example, stricter merger rules could restrict when tech companies can buy out their smaller rivals, a practice that’s common today.

Other rules could prevent large tech companies from favoring their own products, as Google did. These rules could rein in Big Tech’s size and monopoly power (pillar 2).

Another type of proposed reform would make new rules designed specifically for Big Tech’s brave new world. Big Tech can consolidate power in new ways that antitrust doesn’t address. For example, companies “lock in” users to their products by making it difficult to move data to another company’s product or use multiple companies’ products together. Some companies, like Apple, have become infamous for this practice, creating a “walled garden” where only their products work. Tech-specific antitrust rules could knock down the garden’s walls, forcing companies to allow users to freely move their data between companies (a concept called “interoperability”). This is the value proposition of crypto.

What’s been the pushback on reforms?

There’s been a lot of pushback on the suggested antitrust reforms for Big Tech. Critics often point to three major concerns: (1) feasibility, (2) innovation, and (3) the free market.

Feasibility: First, some critics argue that rules, like those that knock down the walled garden, aren’t feasible. They say forcing platforms to work together could create security risks and be too technically difficult to manage.

Innovation: Second, some critics argue that restrictions on behaviors like merging or self-favoring would hurt innovation and competition. They claim such rules would deter venture capital investment in startups and reduce incentives for mature tech companies to innovate, ultimately undermining U.S. competitiveness and global tech leadership.

Free Market: Finally, some critics advocate for free market approach. In this theory, antitrust issues will work themselves out through a sort of natural selection as the industry evolves. For example, Sears dominated retail through its mail-order catalogs and big-box stores but eventually lost ground as it failed to keep up with digital innovation, allowing Amazon to take the lead in online retail.

V. How Has Big Tech Dodged Antitrust Violations Until Now

Big Tech has a long history of staying one step ahead of government regulators on antitrust issues by adapting their strategies to avoid violations and scrutiny. These companies are not only proactive in ensuring compliance but also innovative in finding ways to circumvent potential legal challenges. Here’s how they had been managing to remain ahead:

A. Antitrust Compliance Programs

Until recently, Big Tech had little concern over antitrust investigations, as the long-standing consumer welfare model guiding enforcement remained unchanged for decades. This allowed companies to establish “antitrust compliance” measures—internal processes designed to ensure they operated within legal boundaries and avoided monopolistic practices.

To stay ahead of potential scrutiny, tech companies invested heavily in compliance, creating internal "antitrust filters" to review new products and services. They trained employees on antitrust issues and consulted legal experts to ensure their strategies wouldn’t be seen as anti-competitive. This proactive approach allowed them to avoid legal challenges while continuing to innovate and expand within the boundaries of US antitrust laws. Even when investigations occurred, agencies like the DOJ and FTC often faced limited resources and lengthy timelines, as seen in the Microsoft case, where penalties arrived too late to have significant impact.

After the Google suit, there will be updates to their policies.

B. Avoidance Mergers: Special Dividends and Acqui-Hires and Poaching

Big Tech’s playbook also has included innovative ways to consolidate power without triggering merger rules and government oversight. Big Tech commonly circumvents merger oversight by (1) keeping mergers below reporting thresholds (certain $ deal sizes require a government review), (2) structuring a merger as a different type of transaction, or (3) not technically merging at all.

Special Dividends: First, Big Tech uses a special dividend to keep mergers below the price that triggers reporting and oversight. In this strategy, the company that’s being bought pays its investors a special one-time dividend before the sale, reducing its overall value. This allows the buyer to acquire the company at a lower price, staying under the thresholds that would normally require reporting the deal to regulators.

Acqui-Hires: Second, Big Tech has used acqui-hires to structure mergers as a hiring event rather than a merger that triggers reporting and oversight. An acqui-hire is when a large company buys a startup primarily to gain its key employees. Sometimes, these deals are structured to look like regular employment contracts, hiding the true value of the acquisition by undervaluing the assets and promising future stock options. While these types of deals often go unreported, they can be anticompetitive by benefiting the companies involved while reducing future competition—which ultimately hurts consumers.

Reverse Acqui-hires / Controlling Stakes: Third, Big Tech gains control without outright purchases through reverse acqui-hires and acquiring controlling stakes. Unlike traditional acquihires, where a company is fully acquired mainly for its talent, a reverse acqui-hire involves hiring key employees and licensing a startup’s technology without acquiring the company, allowing it to remain independent. Additionally, purchasing controlling stakes gives Big Tech access to competitors’ confidential information and influence over strategic decisions. For example, Microsoft recently acquired a 49% stake in OpenAI while poaching talent from AI firm Inflection, actions that have attracted antitrust scrutiny in the U.S. and UK.

However, the government is keenly aware of these corporate maneuvers. The real question now is, with the first antitrust domino having fallen, what new strategies will Big Tech devise to navigate this shifting regulatory landscape?

VI. Final Thoughts: The Past And The Future

The exclusive deal between Google and Apple is one of the most significant and consequential in tech history, shaping the competitive landscape of Silicon Valley.

It has allowed Google to solidify its dominance in search while Apple profits without entering the search market directly. This "co-opetition" has effectively shut out rivals like DuckDuckGo and Microsoft’s Bing, undermining claims that Google’s success is purely consumer-driven. Instead, Google’s financial leverage, bolstered by its agreement with Apple, has marginalized competitors and reinforced a closed ecosystem that stifles innovation and blocks new market entrants.

But the far-reaching influence of this deal goes beyond technical dominance. Silicon Valley’s largest companies, including Google and Apple, have not only built powerful businesses but have also leveraged their wealth and influence to shape government policy. The same tech giants now facing antitrust scrutiny have poured millions of dollars into lobbying efforts, creating a formidable political force that protects their interests. In 2024 alone, Google and other Big Tech players have funneled vast amounts of money into political super PACs and lobbying groups, aiming to sway policy in their favor and stave off regulatory threats. In 2023, Big Tech companies, led by giants like Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet, spent $243.7 million on lobbying, making them the second-largest industry in lobbying expenditures, behind only the pharmaceutical sector at $382.6 million. These aggressive lobbying tactics have helped Big Tech stay one step ahead of regulators, shaping antitrust enforcement and slowing down efforts to rein in their power.

The remedy imposed upon Google will truly shape the future of Big Tech. One wonders if the actual remedy will be much reduced as concerns with the US falling behind China on the AI front could push Washington not to threaten US tech dominance. The change in presidential administration adds another layer of intrigue, as it will undoubtedly influence the scope and execution of these remedies – not to mention, it could mean a new inflection point in the enforcement of antitrust laws and direction of the DOJ and FTC.

Even so, when you look at the Microsoft case, even though the remedies were softened, it still paved the way for the rise of Google. The Gilded Age is over at this point and a new Google may emerge from all of this….

VII. Extra Credit: Cases To Keep On Your Radar

With the rise of Khan (sounds like a Star Trek movie) and Kanter and suits brought against Amazon and Google (among others), Big Tech is on notice. Keep the following cases on your radar:

1. Google (2nd Case Focuses on Advertising): A second antitrust case targeting Google’s online advertising practices is currently ongoing, with trial scheduled to wrap-up on November 25, 2024. This case accuses Google of anticompetitive mergers and monopolistic practices in the ad tech space.

2. Amazon: In September 2023, the FTC and 17 states sued Amazon, accusing it of maintaining a monopoly by squeezing sellers and favoring its own services on its marketplace. The FTC claims these practices led to artificially higher prices for consumers. Amazon has asked for the case to be dismissed, arguing that its marketplace benefits both consumers and sellers. The trial is set for October 2026.

3. Apple: In March 2024, the Department of Justice sued Apple, alleging that it monopolized the smartphone market and stifled competition, especially for services like cloud streaming, messaging, and digital wallets. Apple has moved to dismiss the case, claiming that its practices enhance the iPhone experience and don’t violate antitrust laws.

4. Meta (formerly Facebook): The FTC sued Meta in 2020, accusing it of monopolizing social media by acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp to eliminate competition. After some setbacks, the case is proceeding, with the FTC calling for the acquisitions to be undone. Meta argues that the acquisitions were not anticompetitive and contributed to innovation.

5. Visa: The DOJ filed a civil suit in 2024, accusing Visa of monopolizing the US debit network market through exclusionary policies and anticompetitive agreements. Visa allegedly isolated competitors by offering discounts for exclusive routing and paying rivals like Apple and PayPal to avoid developing competing products.

[Special thanks to Sam Silverberg.]

VIII. Resources:

Carl Shapiro, Antitrust in a Time of Populism, 61 Intl. J. Indus. Org. (2018).

Daniel Francis, Christopher John Sprigman, Antitrust Principles, Cases, and Materials 7 (2d ed. 2024).

United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563 (1966).

Amy Hayes, Here’s How John D Rockefeller Became the First Billionaire, THE COLLECTOR (Oct. 12, 2023). thecollector.com/how-john-d-rockefeller-became-first-billionaire/.

Ashkay Jagtap, Aakash Biswas, James Blaney, The Antitrust Legacy of Standard Oil in Today’s World, THE WAY AHEAD (Nov. 1 2021). jpt.spe.org/twa/the-antitrust-legacy-of-standard-oil-intoday’s-world.

Katie Wilson, 1912: When antitrust views collided in a presidential election, CASCADE PBS (Nov. 4, 2020) cascadepbs.org/opinion/2020/11/1912-when-antitrust-views-collided-presidential-election.

R. Hewitt Pate, The Common Law Approach and Improving Standards for Analyzing Single Firm Conduct (Oct. 23, 2003).

Thomas A. Lambert, Defining Unreasonably Exclusive Conduct: The “Exclusion of a Competitive Rival” Approach, 92 N.C.L. Rev. 1175, 1177(2014).

See Mark S. Popofsky, Defining Exclusionary Conduct: Section 2, The Rule of Reason, and the Unifying Principle Underlying Antitrust Rules, 73 L.J. 435, 442 (2006).

Rebecca Klar and Karl Evers-Hillstrom, How Big Tech fought antitrust reform–and won, THE HILL (Dec. 23, 2022) thehill.com/policy/technology/3785894-how-big-tech-fought-antitrust-reform-and-won/.

Bryce Covert, Lina Khan’s Anti-Monopoly Power, THE NATION (Dec. 9, 2023) https://www.thenation.com/article/society/lina-khan-ftc-monopoly.

Andre Fiebig & David Gerber, The Causes and Consequences of the Neo-Brandeisian Antitrust Movement in the United States, DEGRUYTER.COM (Apr. 5, 2021) https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.15375/zwer-2021-0405/html

Andrea O’Sullivan, What Is ‘Hipster Antitrust,’ MERCATUS.ORG (Oct. 18, 2018) https://www.mercatus.org/economic-insights/expert-commentary/what-hipster-antitrust.

Lina Khan & Sandeep Vaheesan, Market Power and Inequality: The Antitrust Counterrevolution and Its Discontents 11 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 235, 237 (2017).

David Streitfeld, Amazon’s Antitrust Antagonist Has a Breakthrough Idea, THE NEW YORK TIMES (Sept. 7, 2018). https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/07/technology/monopoly/-antitrust-era-lina-khan-amazon.html.

Russell Brandom, Amazon says new FTC Chair shouldn’t regulate it because she’s too mean, THE VERGE (Jun. 30, 2021) https://www.theverge.com/2021/6/30/22557456/amazon-lina-khan-recusal-petition-federal-trade-commission-antitrust.

Callum Jones, ‘She’s going to prevail:’ FTC head Lina Khan is fighting for an anti-monopoly America, THE GUARDIAN (Mar. 9, 2024) https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/mar/09/lina-khan-federal-trade-commission-antitrust-monopolies.

Brian Fung & Clare Duffy, Google has an illegal monopoly on search, judge rules. Here’s what’s next, CNN (Aug. 6 ,2024).

David McCabe, Strongest U.S. Challenge to Big Tech’s Power Nears Climax in Google Trial, THE NEW YORK TIMES (May 2, 2024) https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/02/technology/google-antitrust-trial-closing-arguments.html.

Google Antitrust Ruling: A Landmark Decision in the Tech Industry, MONEY MORNING (Aug. 5, 2024), https://moneymorning.com/2024/08/05/google-antitrust-ruling-a-landmark-decision-in-the-tech-industry/.

Jennifer Elias, Google’s antitrust ruling has experts looking to 25-year old Microsoft case for answers, CNBC (Aug. 7, 2024).

Nick Riso, Google Antitrust Ruling: A Landmark Decision in the Tech Industry, MONEY MORNING (Aug. 5, 2024) https://moneymorning.com/2024/08/05/google-antitrust-ruling-a-landmark-decision-in-the-tech-industry/.

Satya Marar, The Antitrust War Against Google Fails Consumers (Sep. 13 2023).

Bill Scher, A Short History of Democrats and Antitrust, WASHINGTON MONTHLY (Jul. 19, 2021) https://washingtonmonthly.com/2021/07/19/a-short-history-of-democrats-and-antitrust/.

Leah Nylen, Huge win for progressives as Lina Khan takes helm at FTC, POLITICO (Jun. 15, 2021) https://www.politico.com/news/2021/06/15/khan-confirm-ftc-494609.

Roger P. Alford, The Bipartisan Consensus on Big Tech, 71 Emory L. J. 895 (2022).

Gregory J. Werden, Identifying Exclusionary Conduct Under Section 2: The “No Economic Sense” Test, 73 Antitrust L.J. 413 (2006).

Steven C. Salop & Craig Romaine, Preserving Monopoly: Economic Analysis, Legal Standards, and Microsoft, 7 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 617, 652 (1999).

Zephyr Teachout, BREAK ‘EM UP; RECOVERING OUR FREEDOM FROM BIG AG, BIG TECH AND BIG MONEY (2020) 214.

Robert Lande, Who Cares Whether A Monopoly is Efficient? The Sherman Act Is Supposed to Ban Them All, THE SLING (Nov. 15, 2023), https://www.thesling.org/who-cares-whether-a-monopoly-is-efficient-the-sherman-act-is-supposed-to-ban-them-all/.

Mark McCareins, Why Antitrust Regulators Don’t Scare Big Tech, KELLOGG INSIGHT (Aug. 19, 2019) https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/why-antitrust-regulators-dont-scare-big-tech.

https://www.history.com/news/robber-barons-gilded-age-wealth

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/07/technology/monopoly-antitrust-lina-khan-amazon.html

https://www.cnn.com/2023/10/16/tech/lina-khan-risk-takers/index.html

https://ainowinstitute.org/publication/antitrust-and-competition

https://time.com/6116953/antitrust-reform-big-tech-congress-biden/

https://www.csis.org/analysis/breaking-down-arguments-and-against-us-antitrust-legislation

https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/why-antitrust-regulators-dont-scare-big-tech

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/05/technology/antitrust-google-amazon-apple-meta.html

https://www.reuters.com/legal/us-judge-rules-google-broke-antitrust-law-search-case-2024-08-05/

https://slate.com/technology/2024/08/google-monopoly-antitrust-decision-defeat-big-tech.html

https://www.cato.org/regulation/winter-2023-2024/neo-brandeisianisms-democracy-paradox

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/10/14/silicon-valley-the-new-lobbying-monster

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/25/technology/apple-google-search-antitrust.html

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-which-u-s-industries-spend-the-most-on-lobbying/

https://ainowinstitute.org/publication/antitrust-and-competition

https://time.com/6116953/antitrust-reform-big-tech-congress-biden/

Images: All images are AI-generated with using a combination of Dall-E, Firefly, DreamStudio and Pixlr.

Disclaimer: This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. This post reflects the current opinions of the author(s). The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.